Fibrin Sealant and Lipoabdominoplasty in Obese Grade 1 and 2 Patients

Article information

Abstract

Background

Ever since lipoabdominoplasty was first developed to achieve better aesthetic outcomes and less morbidity, the rate of seroma formation, especially in obese patients, has disturbed plastic surgeons. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of fibrin sealant in the prevention of seroma formation after lipoabdominoplasty in obese patients.

Methods

Sixty patients with a body mass index (BMI) between 30 and 39.9 were assigned randomly to 1 of 2 groups (30 patients each). Group A underwent lipoabdominoplasty with fibrin glue, while group B underwent traditional lipoabdominoplasty; both had closed suction drainage applied to the abdomen. The patients' demographics and postoperative complications were recorded. Seroma was detected using abdominal ultrasound examinations at two postoperative periods: between postoperative days 10 and 12 and, between postoperative days 18 and 21.

Results

The age range was 31 to 55 years (38.5±9.5 years) in group A and 25 to 58 years (37.8±9.1 years) in group B, while the mean BMI was 31.4 to 39.9 kg/m2 (32.6 kg/m2) in group A and 32.7 to 37.4 kg/m2 (31.5 kg/m2) in group B. In group A, the patients had a complication rate of 10% in group A versus 43% in group B (P<0.05). The incidence of seroma formation was 3% in the fibrin glue group but 37% in the lipoabdominoplasty-alone group (P<0.05).

Conclusions

Lipoabdominoplasty with the use of autologous fibrin sealant is a very effective method that significantly reduces the rate of postoperative seroma.

INTRODUCTION

The combination of liposuction with abdominoplasty has spurred a wide-ranging debate about its effects on flap vascularity and viability. Careful anatomical studies by Huger [1] led to the description of safe zones for careful liposuction in combination with abdominoplasty, and since then, many refinements to the procedure have been made, with the aim of good aesthetic results with minimal postoperative complications [2,3].

Hematoma, superficial desquamation, and skin necrosis were decreased with the development of the lipoabdominoplasty technique. However, postoperative seroma remains an ongoing problem, and the data on its incidence is inconsistent [4]. Some preventive measures have been recommended to reduce the incidence of postoperative seroma, including minimal handling of the skin flap, quilting sutures, use of drains, and the wearing of compression garments during the postoperative period [5,6].

Tissue adhesives have been used to provoke adhesion of the surfaces in many surgical situations and have assisted in reducing the need for drainage and minimizing the rate of postoperative seroma [7,8].

Most of the studies that have been performed concerning postoperative seroma have included only individuals with normal body mass index (BMI) scores. Therefore, in our study we performed lipoabdominoplasty on obese grade 1 and 2 patients using fibrin glue, to augment previous studies searching for biological sealants to decrease the rate of seroma formation.

METHODS

The study was carried out over a period of 3 years. Sixty patients were included with a predominance of women (women, 58; men, 2). Thirty patients underwent lipoabdominoplasty with the use of autologous fibrin glue, and the other 30 patients underwent traditional lipoabdominoplasty. All of the patients had Rohrich type IV B deformities [9] (significant skin and fat excess with diastasis of the rectus muscle), and their BMI scores were equal to or greater than 30 and less than 40 (i.e., obese grade 1 and 2 according to the International Classification of Adult Underweight, Overweight and Obesity according to BMI developed by the WHO) [10].

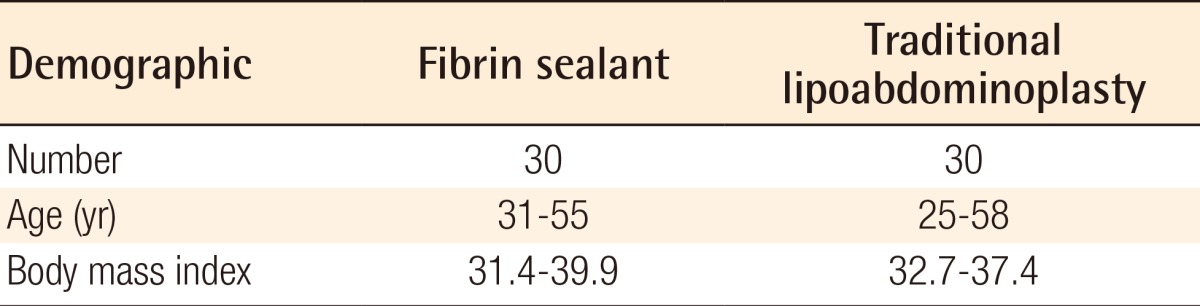

The patients' ages ranged between 31 and 55 years (38.5±9.5) in the fibrin glue group and ranged between 25 and 58 years (37.8±9.1) in the traditional lipoabdominoplasty group. The BMI scores of the patients undergoing fibrin glue application ranged from 31.4 to 39.9, with an average of 32.6. In the patients who underwent traditional lipoabdominoplasty, the BMI ranged from 32.7 to 37.4, with an average of 31.5 (Table 1).

Smokers and patients with a history of diabetes, cardiac problems and vascular diseases, previous abdominal surgery, or complaints of umbilical or paraumbilical hernias, or who had experienced significant weight loss were excluded from the study.

The surgical technique was performed similarly in both groups except for the fibrin sealant application: 1) Marking was done first by drawing a 12-cm horizontal supra-pubic line that was 7 cm from the vulvar commissure. Two oblique lines of 10 cm each were drawn in the direction of the iliac crest; then the liposuction areas were marked. 2) Venous blood was drawn into a tube containing an anticoagulant (citrate dextrose) to avoid platelet activation and degranulation (50 mL). The first centrifugation, called the "soft spin" (3,600 rpm), allows blood separation into three layers, namely the bottom-most RBC layer (55% of total volume), topmost acellular plasma layer called platelet poor plasma (PPP) (40% of total volume), and an intermediate platelet-rich plasma (PRP) layer (5% of total volume) called the "buffy coat". This tube underwent a second centrifugation (2,400 rpm), called the "hard spin". This allowed the platelets (PRP) to settle at the bottom of the tube with a very few red blood cells. The acellular plasma, PPP (80% of the volume), was found at the top. Most of the PPP was removed with a syringe, and the remaining PRP was shaken well [11]. This PRP was then mixed with bovine thrombin (0.2 mL for every 1 mL of PRP) and 10% calcium chloride (0.1 mL) at the time of application in a petri dish. 3) The super wet technique for infiltration of the supraumbilical region and flanks was carried out using a 1:500,000 adrenaline/saline solution; then liposuction using 4-mm and 5-mm cannulas to remove the fat of the deep and superficial layers was performed. The volume of the lipoaspirate was an average of 3,200±780 mL with an average infiltrate of 3,500±600 mL for group A, while in group B the lipoaspirate was 3,150±730 and the average infiltrate was 3,300±560. The fat thickness was maintained at about 2.5 cm to avoid vascular impairment and contour deformities. 4) After liposuction, a central lower abdominal incision was made down to the level just above the muscle, dissecting the abdomen using a scalpel to the level of the umbilicus. After dissection and trimming of the umbilicus stack; the dissection was continued superiorly to the xiphoid, with lateral dissection up to 7.5 cm from the midline. 5) Plication of the recti was completed in two layers, followed by removal of the excess infraumbilical skin. A V-shaped incision was made 2 cm above where the umbilical position was marked for exteriorization of the umbilicus; then a total of 20 mL of platelet gel was applied in group A patients starting from the xiphoid process to the incision, with continuous external pressure applied to the abdomen after application of every 5 mL until the end of the closure of the incision (Fig. 1). 6) Placement of 2 silicone suction drains was done in both groups, followed by closure of Scarpa's fascia using PDS (2-0) suture. The dermal and subcuticular layers were then sutured using PDS (3-0) suture. A non-adhesive dressing like Vaseline gauze was used.

Application of the fibrin sealant

In group A, after the limited dissection of the abdominal flap and plication of the rectus muscles, application of the fibrin glue is performed just before skin closure.

Postoperatively, the patients were encouraged to ambulate within 12 to 18 hours. All of the patients in both groups were hospitalized for 5 days with administration of antibiotics, analgesics, and antiedema medications until the drains were removed when the daily drainage volume was less than 30 mL, which was on the 5th day in most cases, and the patients were then discharged. The sutures were removed by the 15th day. Use of the compression garments was continued for 4 weeks.

All of the patients underwent abdominal ultrasound examinations at 2 postoperative periods: 1) between postoperative days 10 and 12 and, 2) between postoperative days 18 and 21. The examinations were performed by the same examiner using an ultrasound system (Antares, Siemens, Brazil); longitudinal, transverse, and oblique scans of the 5 abdominal regions were made. A total volume of 20 mL of liquid from the 5 regions were considered positive for seroma, and an ultrasound-guided puncture was performed for drainage of the seroma.

Preoperative and postoperative digital photographs were taken at least one month after the operation and every six months thereafter using a Nikon Coolpix P500 digital camera (12.1 Mpx, 36X optical zoom, Tokyo, Japan). The follow-up period ranged from six to twelve months.

Statistical analysis of the results was performed by MedCalc software ver. 9.6.2.0 (Mariakerke, Belgium). The results are expressed as mean+standard deviation. Wilcoxon's rank sum test was used for comparisons of same-group paired data. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant. With small sample sizes in groups, only very strong differences between groups can be detected.

RESULTS

In all of the patients and both techniques, there were no deaths, major complications, anesthesia complications, or deep vein thrombosis. All of the patients suffered from pain, ecchymosis, and edema postoperatively, but to varying degrees. The pain was moderate and decreased gradually over time. However, the ecchymosis was severe but disappeared completely after 3 weeks. Edema and indurations occurred, but to a moderate degree, and declined gradually, disappearing after 4 to 6 weeks (Figs. 2, 3).

An example from the group A patients

A 31-year-old female with a body mass index of 32 (A, B) show the anteroposterior view preoperatively and postoperatively, (C, D) show the left oblique view preoperatively and postoperatively, (E, F) show the right oblique view preoperatively and postoperatively.

An example from group B patients

A 36-year-old female with a body mass index of 36.9 from group B (A, B) show the anteroposterior view preoperatively and postoperatively, (C, D) show the right oblique view preoperatively and postoperatively, (E, F) show the left oblique view preoperatively and postoperatively.

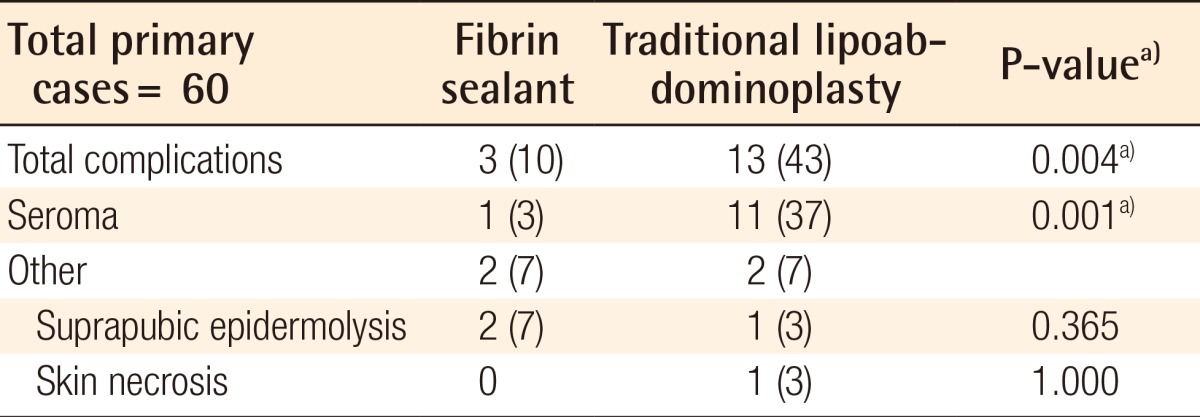

The total complication rate in group A was 10% (n=3), which was significantly less than the rate for group B, at 43% (P=0.004). Concerning seroma formation, only 3% of the cases (n=1) had collections detected by abdominal ultrasound during both periods for patients undergoing fibrin glue application, which was significantly less than the incidence in the traditional lipoabdominoplasty group of 37% of the cases (n=11) (P=0.001). These patients with seromas underwent ultrasound-guided aspiration two times weekly until clinical resolution with no uneventful consequences related to the seroma or drainage.

Other than seroma, there was no difference in the skin necrosis rate (fibrin glue, 0%; traditional lipoabdominoplasty, 6.7%) or suprapubic epidermolyses (fibrin glue, 6.7%; traditional lipoabdominoplasty, 10%) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Since Callia's original description of abdominoplasty in 1963, this technique has evolved greatly in response to demands for better results, smaller scars, faster postoperative recovery, and, above all, fewer postoperative complications [12].

The first description of the association between lipoplasty and full abdominoplasty was reported in 1991 by Matarasso [13], who performed lipoplasty of the abdominal flap with wide undermining and classified the areas that could be aspirated on the basis of the blood supply of the abdominal wall. He stated that the lateral and superior areas are safe, while the central medial flap must be suctioned cautiously.

As the work by Saldanha et al. [14] demonstrated no increased complications when liposuction was added to full abdominoplasty, this fear has begun to dissipate, with lipoabdominoplasty becoming a more commonplace procedure.

Although this technique has gained a huge popularity, many surgeons have performed it only for patients with normal BMI scores with good results. In 2009, Brauman and Capocci [3] performed lipoabdominoplasty on 337 consecutive patients with an average BMI of 29.3 kg/m2 (range, 19.5-41.7 kg/m2). The authors observed that seroma (5 cases; 1.4%) occurred more frequently in patients with high BMI scores, massive weight loss, and following diastasis repair.

This is not the case in our country, where a BMI over 30 kg/m2 is a common finding; thus in the present study, we tried to assess the applicability of lipoabdominoplasty in obese patients having BMIs ranging from 30 to 39.9 in light of the postoperative complication rate and aesthetic outcome.

Few studies have been published concerning the rate of complications among the patients who underwent lipoabdominoplasty and had a high BMI. Heller et al. [2] detected the presence of seroma, but at a lower rate in comparison with abdominoplasty alone in 31 patients (BMI ranging from 19.9 to 39.3 with a mean of 28.2) who underwent a combined procedure of abdominal liposuction and inverted V-pattern abdominoplasty. Rangaswamy [15] detected no seroma in his last 100 patients from 120 patients, among whom 90% were either clearly obese or overweight with a mean BMI of 33.

Rather than the frequent refinement of the lipoabdominoplasty procedure, postoperative seroma was common, but the incidence was less than in conventional abdominoplasty and many studies have been performed with the aim of reducing it [16,17].

Khan [18] applied progressive tension sutures, which had been previously described by Pollock and Pollock [19], to his lipoabdominoplasty cases to reduce the incidence of seroma, and he found that the rate did decrease but did not disappear.

In 2010, a study by Di Martino et al. [20] proved that patients who had abdominoplasty with quilting sutures and those who had lipoabdominoplasty both had a lower incidence of seroma than conventional abdominoplasty. However, the authors operated upon patients with a BMI lower than 30 kg/m2, which is not always the case in patients seeking abdominoplasty in our country.

Fibrin glue functions as a tissue sealant through the formation of a fibrin clot initiated by activation and aggregation of platelets. The fibrin clot then provides a matrix for the migration of tissue forming cells and endothelial cells involved in angiogenesis and the remodeling of the clot into repair tissue. The use of fibrin sealants under the skin flap prior to closure is well accepted and significantly reduces prolonged wound drainage and seroma formation [21].

Walgenbach et al. [22], conducted a trial on patients undergoing abdominoplasty to assess the use of a lysine-derived urethane adhesive (TissuGlu, Cohera Medical, Pittsburg, PA USA). They found that the mean total drain volume tended to be lower than in the control patients who underwent an identical procedure but without application of TissuGlu. In their study, they treated patients with normal BMI scores, and they did conventional abdominoplasty without liposuction or quilting sutures but with the use of synthetic glue; their results showed a decreased rate of postoperative seroma.

In a preliminary study done by Schettino et al. [23], they analyzed data from 12 patients undergoing abdominoplasty using autologous plasma in its less platelet-concentrated portion (biological glue) and they found a reduction in postoperative collections, mainly seroma. The present study was carried out on 30 patients with high BMI scores who underwent lipoabdominoplasty with the usage of fibrin glue to obliterate the present dead space, and only 1 case of seroma formation occurred after removal of the drains.

To conclude, our study augments other recent studies [24,25] that report the promising outcomes of the usage of autologous fibrin sealant with lipoabdominoplasty. This technique seems to reduce postoperative seroma; however, to compensate for the limitations of our study, more studies with larger sample sizes and power analysis, as well as research on the cost of fibrin sealants and the duration of surgery are needed.

Lipoabdominoplasty with the use of autologous fibrin sealant is a very effective method that significantly reduces the rate of postoperative seroma.

Notes

This article was presented at the 41st Annual International Congress of the Egyptian Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons in on October 27-30, 2011 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.