Surgical Resection of Acquired Vulvar Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

Article information

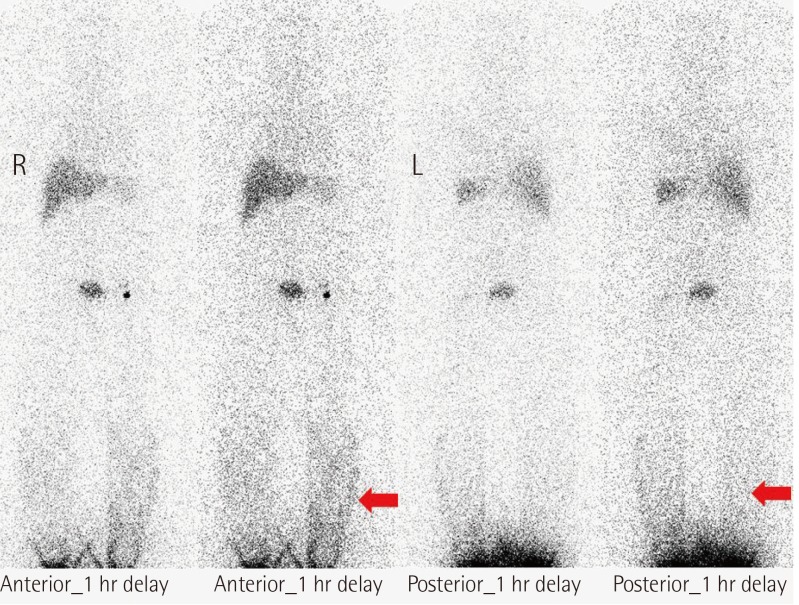

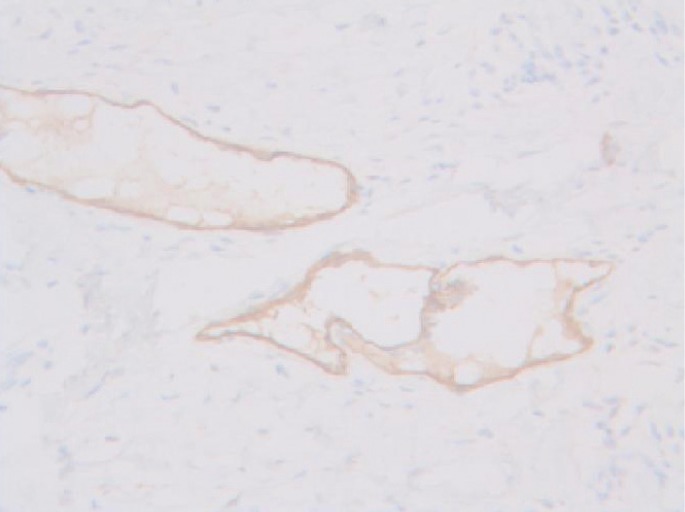

The predominant types of lymphangioma are lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC), cavernous lymphangioma, cystic hygroma, and lymphangioendothelioma. These entities account for approximately 26% of benign vascular tumors in children but are rarer in adults [1]. LC is the most common form of cutaneous lymphangioma and is characterized by superficial lymphatic ducts protruding through the epidermis. Whimster postulated that lymph sacs that are lined by muscle fibers contract and result in outpouching, which eventually causes skin protrusions to become what are clinically described as vesicles [2]. This condition results in clusters of clear fluid-filled vesicles resembling frog spawn and associated tissue edema. It is usually found on the proximal extremity, trunk, and axilla, which has an abundant lymphatic system, but rarely involves the vulva, penis, scrotum, gingiva, tongue, and even the conjunctiva. Vulvar LC is a debilitating condition, causing lymphedema, itching, eczema, oozing, sexual dysfunction, and infection. It is very rare and either a congenital or an acquired condition following damage to previously normal lymphatics. Radical hysterectomy with subsequent radiotherapy appears to be the only recently recognized acquired risk factor. Although there are many other treatment modalities, surgery, particularly major labiectomy, has been reported to be the best treatment option for the potential of early rehabilitation and low recurrence. A 71-year-old female presented to our outpatient clinic with persistent edema of both lower limbs, clusters of pink labial papules, pruritus, and watery lymph oozing. Her condition had been deteriorating for 5 years without any treatment. These cutaneous symptoms began with a few vesicles 24 years after radical hysterectomy with adjuvant pelvic radiation therapy under the diagnosis of stage IIb squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix (Fig. 1). There was no history of sexually transmitted disease or gastrointestinal disease. Bilateral vulvar edema with vesicular skin eruption was found on colposcopy and a cervical smear showed normal findings. Radioisotope lymphoscintigraphy showed a decreased lymphatic uptake in the pelvis and the dermal back flow of lymphatics in both lower legs, which implied lymphatic obstruction (Fig. 2). Preoperative biopsy revealed probable cavernous lymphangioma. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia in the lithotomy position with a urinary catheter. We removed all the papules by performing bilateral major labiectomy down to the level of Colles' fascia, sparing the clitoris and fourchette (Fig. 3). The extent of the subcutaneous excision was determined by preoperative pelvic computed tomography and intraoperative findings such as wetness, presence of cysts, and fibrous components. After the excision, the wound was closed primarily. Surgical biopsy showed multiple dilated lymph vessels, which is a histological feature of LC. There was no endothelial swelling representing lymphangitis or a granulomatous reaction. The postoperative course was uneventful. There was a clear improvement in the symptoms such as oozing, itching, and rubbing by the time of follow-up at 6 months after surgery, yet further follow-up is considered necessary (Fig. 4). Vulvar LC is an uncommon entity with various clinical mimics like genital warts, herpes zoster, molluscum contagiosum, leiomyoma, and recurrent carcinoma. Further, this makes the biopsy of the lesion essential to differentiate various infective diseases and other tumors. Since the lesions may appear papillary upon histological analysis, a specific lymphatic endothelial marker such as D2-40 is necessary to reduce the diagnostic difficulty [3]. In our case, we used D2-40 stains as is and obtained positive findings (Fig. 5). When lymph nodes are affected, fluid formation exceeds the lymphatic transport capacity, and this makes the affected region more prone to infection and the consequent fibrosis. However, it is not known why most patients who have undergone regional node dissection do not develop lymphedema. Although radical hysterectomy with or without radiotherapy is believed to be the only recognized cause of LC, there are various other reported conditions that lead to LC, such as Crohn's disease, urogenital tuberculosis, bacterial infections, and non-gynecologic tumors. Thus, thorough patient history-taking is essential to identify factors suggesting this rare condition and prevent delay in treatment. Thus far, there is no definite treatment of choice for LC because the number of reported LC cases is too small to conclusively determine the best treatment modality. There are various non-surgical treatments ranging from conservative management with massage, exercise, compression, and sclerotherapy, to CO2 laser therapy depending on the type and extent of LC. Recently, CO2 laser therapy has been used often as the main alternative to surgery. However, in some cases, particularly in those with deep lesions, it caused pain and exacerbation of vesicles and vulvar keloid formation [4]. Unlike conservative treatment options, surgical management offers a more permanent solution. Although many other surgical treatment modalities, including the insertion of polythene tubes, lymphovenous anastomosis, and lymph angioplasties have been reported, labial reduction or excision of edematous tissue seems to show more promising results since it can be repeated as necessary until both the functional and the aesthetic goals are achieved. It is known that the size of the lesion also affects the surgical outcome and the recurrence rate. Browse et al. [5] reported a high recurrence rate after radical excision when the initial lesion was larger than 7 cm compared with a lesion less than 7 cm in size for which only a local excision was performed. However, in our case, no recurrence was found despite the fact that the lesion was approximately 9 cm×3 cm in size. We reported our experience of major labiectomy as the surgical management of LC in one patient who had remission with no recurrence. This might be just another case report of surgical resection of LC, but because of a lack of cases, we believe that this report can contribute to finding the best modality for the management of LC.

Radioisotope lymphoscintigraphy showing dermal back flow (red arrows) of the lymphatics in both legs.

D2-40 staining marking lymphatic endothelial cells lining the dilated intraepidermal lymphatic space (×200).

Notes

This article was presented as a poster at the70th Congress of the Korean Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery on November 9-11, 2012 in Seoul, Korea.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.