A Rare Case of Postoperative Traumatic Optic Neuropathy in Orbital Floor Fracture

Article information

An orbital blowout fracture is a commonly occurring facial trauma that accounts for 7.6% of isolated facial fractures [1], and despite a proper surgical technique, complications are still observed at long-term follow-up, for example, diplopia, enophthalmos, hypesthesia of the infraorbital nerve territory and although rare, optic neuropathy. Among these complications, optic neuropathy is a potentially blinding complication. The most common form of traumatic optic neuropathy is an indirect injury to the optic nerve due to intraorbital hemorrhage, vascular insufficiency or a nerve sheath injury whereas direct damage to the optic nerve during dissection and insertion of implant materials is also possible.

We report a case of a patient with postoperative traumatic optic neuropathy due to indirect nerve damage after traction force might be applied to release a severe adhesion during a dissection procedure.

A 35-year-old female patient was referred from the ophthalmology department complaining of enophthalmos on her right eye and presented for surgical correction of a right-sided upward gaze limitation. The problem was first found 2 years prior to visit after she was hit by a slamming door, but the patient did not receive immediate treatment at that time.

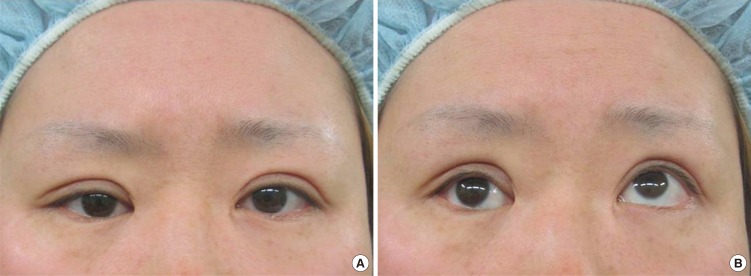

A physical examination revealed right-sided enophthalmos (3 mm) and restricted mobility of the right eye during upward gaze without a visual defect (Fig. 1). The difference in anteroposterior position between the eyes was measured by Hertel exophthalmometry. Small amounts of enophthalmos (less than 3 mm) are not easily detectable and clinically insignificant but larger fractures of the orbital walls could result in severe enopthalmos (3 mm or greater) which is easily noticeable with blind eye [2].

(A) Patient with posttraumatic enophthalmos and hypoglobus of the right eye. (B) Upward gaze limitation was noted on preoperative day 1.

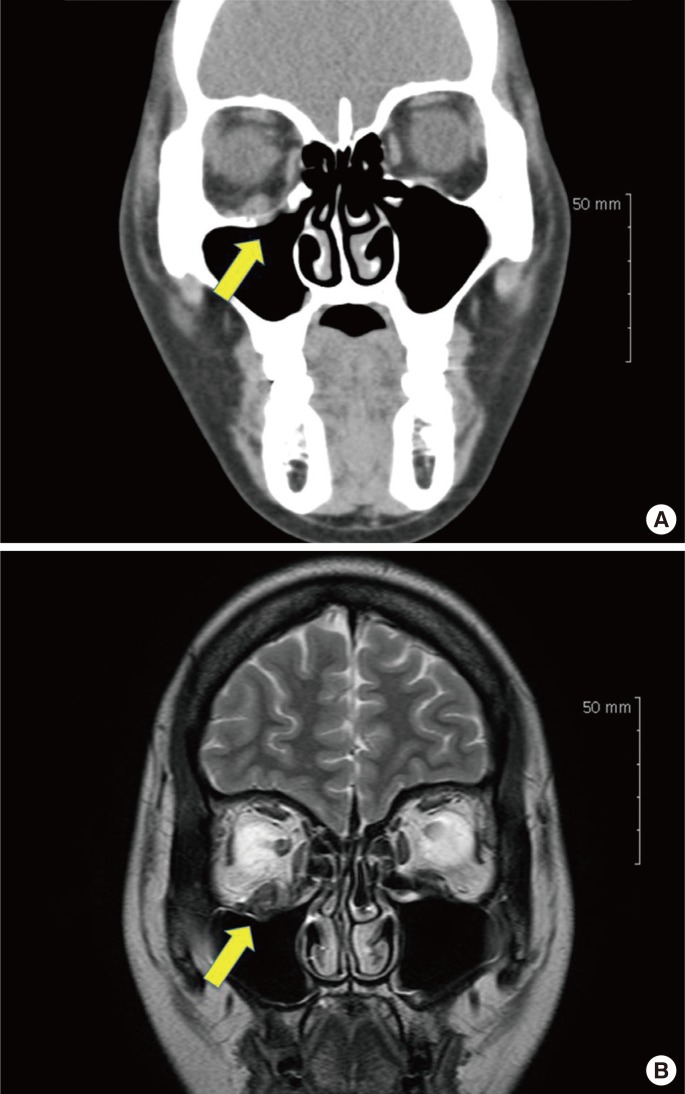

Visual acuity was within the normal range on the right 0.9 and left sides 0.7. Computed tomography (CT) images showed a focal bony defect and herniated inferior rectus muscle and fat at the medial aspect of the inferior wall of the right orbit (Fig. 2).

Coronal images showed an orbital floor fracture (yellow arrow) with inferior rectus muscle herniation.

The orbital periosteum was incised on the inferior orbital rim sharply through a subcilliary incision under general anesthesia. Thickened fibrotic tissue was noted between the periorbita and the fracture site where a 2.0×1.6 cm sized bony defect was found. Dissection was difficult because of the severe adhesion surrounding the inferior rectus muscle and scar formation over the superior orbital fissure and the posterior orbit. An orbital tissue herniation including the inferior rectus muscle was released, and the orbital floor was reconstructed using a 2.0×3.0 cm synthetic resorbable implant. On postoperative day 2, the patient complained of diplopia in the field of superior and inferior gaze and blurred vision. Physical examination revealed that the restriction of vertical eye movement was still remaining and superior visual field defect was developed with decreased visual acuity from 0.9 to 0.15. No evidence of optic nerve compression was detected on the immediate postoperative CT images and improvement of the right inferior rectus muscle herniation was observed (Fig. 3A). The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg qid for three days and the synthetic resorbable implant was removed under local anesthesia on the second day after the operation. Mild fibrosis and thickening around the inferior rectus muscle was confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging 3 weeks after surgery without direct optic nerve injury (Fig. 3B). Mild visual improvement from 0.15 to 0.3 was detected at the patient's last follow up at 5 months after surgery.

(A) Postoperative computed tomography scan showed orbital floor reconstruction with synthetic resorbable implant and improvement of the herniation of inferior rectus muscle (yellow arrow). (B) Postoperative coronal magnetic resonance image revealed no compression on the optic nerve but thickening of the inferior rectus muscle was noted (yellow arrow).

The goal of surgery for this patient was to release the impingement of the orbital contents and reconstruct a functional orbit [2]. The most frequent cause of postoperative optic neuropathy is an increase in intraorbital pressure in the optic canal, as even small changes in pressure may potentially cause ischemic optic neuropathy. In our case, intravenous and oral corticosteroid was given after surgery to decrease edema and pressure but there was no significant recovery of visual acuity. The possibility of direct injury to the optic nerve was low as we performed the dissection no more than 3.0 cm from the margin of the inferior orbit. The depth of the orbit is 3.5 to 4.5 cm from the margin of the inferior orbit to the optic foramen [3]. But, in our opinion, as the fibrous adhesion was severe, indirect injury due to traction force during complete dissection appeared to be the cause of the traumatic optic neuropathy in this patient. To maintain a safe distance (dissection no more than 3.0 cm from the margin of the inferior orbit) from the optic nerve with in the orbit, we using a periosteal elevator with a pen mark as a guide during the operation. Surgical mechanical stress may also impair the extraocular muscle and aggrevate swelling of the orbital contents and could result in traumatic optic neuropathy [4]. Many mechanisms, such as intraoperative direct optic nerve damage, and retinal arteriolar occlusion associated with orbital edema have been implicated in postoperative optic neuropathy. Among these, indirect damage to the optic nerve and its surrounding orbital structures appear to be the most common cause [4].

The postoperative traumatic optic neuropathy is an uncommon, but potentially serious complication. Optic nerve contusion or compression can result in a total loss of vision. Also hematoma, ischemia or direct bone fragment penetration of the optic nerve may be the cause [5]. Treatment with immediate decompression of the optic nerve and high doses of corticosteroids remains controversial [4]. Based on our patient's experience, the dissection in the posterior orbit might be compromised when treating old orbital blowout fracture with severe scarring occurred in the posterior orbit as it is not adequately treated initially. So, the plastic surgeons should maintain safe distance, no more than 3.0 cm from the margin of the inferior orbit, rather than placing these structures at risk [4].

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.