The superior lateral genicular artery flap for reconstruction of knee and proximal leg defects

Article information

Abstract

Reconstruction of defects around the knee region requires thin and pliable skin. The superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) flap provides an excellent alternative to muscle-based flaps. The anatomy and the surgical techniques of the SLGA flap were reviewed and the results of cases using the SLGA flap for coverage of knee and proximal leg defects were analyzed. SLGA flaps were performed in two cases and followed up for at least 6 months. Twelve articles on the use of the SLGA flap were also identified. A review of 39 cases showed that the mean diameter of the perforator supplying the skin of the flap was 1.04 mm, while the mean diameter of the SLGA at its origin was 1.78 mm. The mean length of the pedicle measured from the origin of the popliteal artery was 7.44 cm. The average dimensions of the flap were 14.8×6.6 cm with primary closure of the donor site in 61.5% of cases. Of these cases, 38.5% were due to trauma, 23.1% were post-burn complications, 12.8% were defects after resection of tumors, and 10.3% were for ulcers post-bursectomy. The most common complication was flap tip necrosis. All studies reported favorable outcomes with complete wound healing.

INTRODUCTION

The knee joint is a mobile region requiring thin and pliable tissue to optimize movement. While muscle flaps are commonly seen as the workhorse flaps in this region, they are bulky and lack the ability to provide like-for-like reconstruction for skin defects. Cosmesis is poor and there is notable donor site morbidity [1].

Pedicled perforator flaps offer like-for-like reconstruction, decreased donor site morbidity, a technique that is technically less demanding than free tissue transfers, and a donor site limited tothe same area [2]. The superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) flap is an alternative to muscle flaps. This study reviewed the relevant anatomy and analyzed the results of using this flap for coverage of peri-knee defects.

The SLGA flap was originally reported by Hayashi and Maruyama [3] in 1990. Prior to this, Laitung [4] had reported the possibility of utilizing this flap based on cadaveric studies. In 1995, Spokevicius and Jankauskas [5] described a flap based on the SLGA that had consistent anatomy, a long pedicle, and minimal donor site morbidity

In 2005, Zumiotti et al. [6] conducted a study to verify the anatomical reliability of the flap and performed the flap successfully in four patients. Nguyen et al. [7] conducted a similar study in 2011 that clearly mapped the perforator territories in relation to standard bony landmarks.

From November to December 2017, SLGA flaps were performed to cover knee and proximal leg defects in two male patients, aged 24 and 46 years, respectively. Both had been injured in traffic accidents.

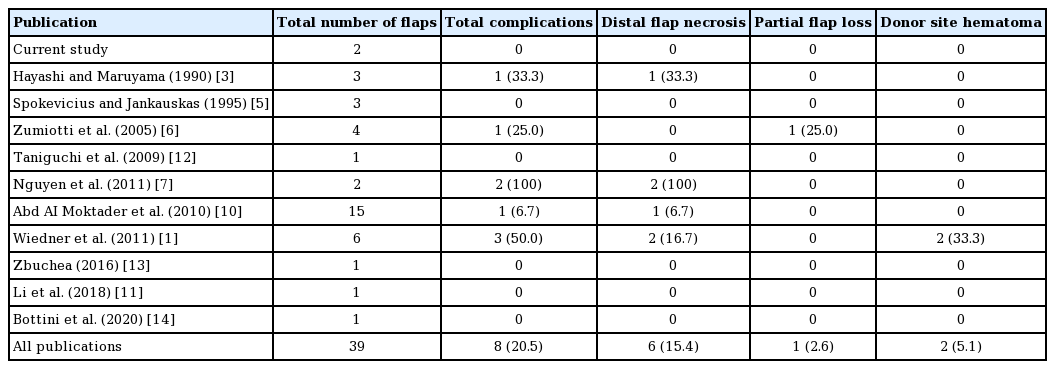

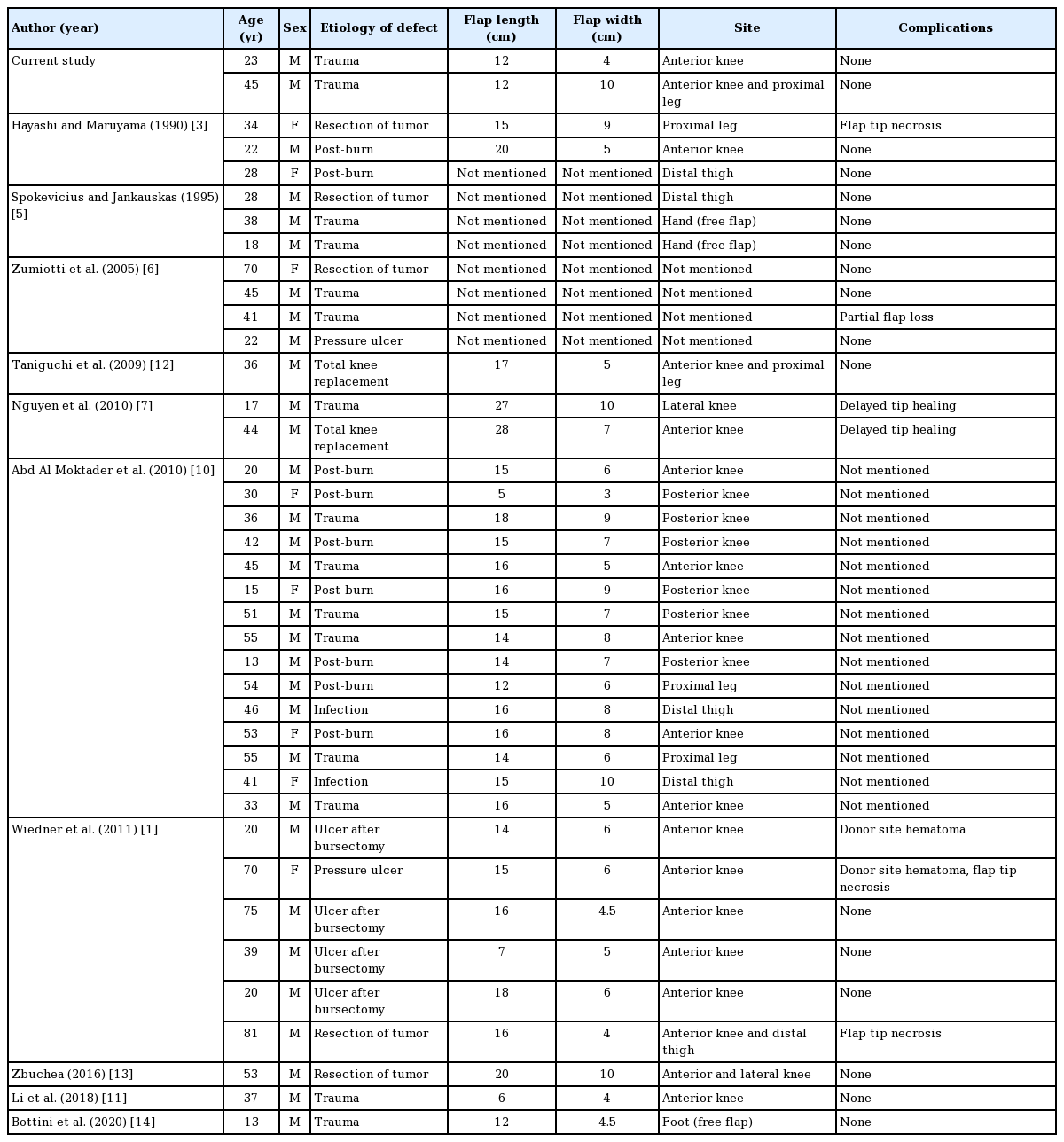

A review of the literature was conducted utilizing PubMed, with the keywords “superior,” “lateral,” “genicular,” and “artery.” Twelve articles pertaining to the use of the SLGA flap were identified: two cadaveric studies [8,9], four combined cadaveric studies and case series [3,5-7], three case series [1,10,11] and three case reports [12-14]. Data pertaining to anatomy, patient characteristics, etiology, surgical details, and complications were compiled and the results were summarized (Tables 1-3).

Compilation of cases showing the clinical characteristics of superior lateral genicular artery flaps

Comparison of anatomical characteristics of the superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) from cadaveric studies

The SLGA originates from the popliteal artery at a mean distance of 40.07 mm proximal to the knee joint with a mean diameter of 1.78 mm at its origin [8]. It courses posterior to the femur in a superolateral direction until reaching the lateral intermuscular septum, where the SLGA pierces the deep fascia proximal to the lateral condyle of the femur and divides into superficial and deep branches [10]. The mean length from the origin of the SLGA to its termination is 7.44 cm [8].

At the point where the SLGA divides into superficial and deep branches (about 50 mm from the plane of the knee joint) [10], a consistently sizable cutaneous perforator emerges, running posterolaterally to supply the lateral skin of the thigh [7]. This cutaneous perforator terminates in small cutaneous branches and communicates with the lateral perforators of the profunda femoris (Fig. 1) [3].

A reliable skin perforator was always present. Among the 28 lower limbs dissected by Nguyen et al. [7], there were, on average, 1.89 perforators per limb. A study by Zumiotti et al. [6] found that in 36 lower limbs 40% of the perforators followed an intramuscular course. In the study by Nguyen et al. [7], the mean distance of perforators from the superolateral patella was 5.3 cm, while Zumiotti et al. [6] reported a mean distance of 7.4 cm from the lateral condyle of the femur (Fig. 2). Gstoettner et al. [9] showed a constant SLGA angiosome with a mean size of 222.8 cm2 over the anterolateral proximal knee joint.

Anatomy and design of the superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) flap. (A) The territory of the SLGA flap and its perforators. The skin island can be designed from the lateral condyle of the femur up to the midpoint between the great trochanter and the lateral condyle. The perforator(s) typically penetrate the fascia 30–80 mm proximal to the lateral femoral condyle. (B) After perforator selection, the flap is islanded and rotated about the pivot point into the defect. (C) Transposition of the flap into the knee/proximal leg defect with primary closure of the donor site.

Potential perforators were marked, with Doppler assistance, 5–8 cm proximal to the lateral femoral condyle. The skin island of the flap was designed on the lateral aspect of the lower thigh, with the proximal limit at the midpoint between the greater trochanter and lateral femoral condyle [10].

Only one edge of the planned flap was initially incised, so that it could then serve as the edge of an alternative flap if a suitable perforator was not found [15]. The flap was raised in the subfascial plane with all potential perforators isolated and preserved. A perforator of suitable size, with visible pulsation and accompanying venae comitantes, is a better indicator of perforator reliability than the Doppler assessment. The other edge of the flap was subsequently incised, with a skin bridge left at the base of the flap adjacent to the selected perforator as an additional source of perfusion (Fig. 3).

Superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) flap raising and inset. (A) SLGA flap with an intact skin bridge adjacent to its perforator, shown by a red dot. (B) Transposition of the flap into the defect with the skin bridge left intact. (C) Dog-ear present at pivot point after inset of flap.

A decision was then made about whether to island the flap or leave the previously mentioned skin bridge, which would limit the flap rotation to 90°–120°. For a variety of reasons (e.g., small caliber, poor flow, or traumatized vessel) the perforator was occasionally insufficient to support the flap. In this case, leaving a skin bridge added an additional random pattern blood supply. A soft bowel clamp was applied over the skin bridge to obstruct blood flow and then the flap was observed for approximately 10 minutes. If there was no clinical compromise, the flap could be islanded. Otherwise, the skin bridge was kept.

The donor site was then closed, or grafted if the defect was too wide. If the closure was excessively tight, the region around the pivot point could be skin grafted to minimize tension near the pedicle. If a dog-ear was present at the proximal aspect of the donor site wound post-closure, the dog-ear could be excised and the skin from the excised portion could be used to graft the region around the pivot point (Fig. 4).

CASE

Both our flaps survived with good functional outcomes. Closure of the donor site was achieved for the first case, while the donor site in the other case was skin-grafted. Both wounds healed completely after 6 months.

In our literature review, a total of 37 clinical cases of SLGA flaps were identified. Adding our two cases, we performed a review of 39 clinical cases (Table 1).

Based on the anatomical data (Table 2), the mean diameter of the perforator supplying the skin of the flap was 1.04 mm, while the mean diameter of the SLGA at its origin was 1.78 mm. The mean length of the pedicle measured from the origin of the popliteal artery was 7.44 cm.

The average age of patients in all studies was 38.4 years, with an average flap width of 6.6 cm and length of 14.8 cm. Eighteen cases involved the anterior knee, six cases involved the posterior knee, five cases involved the proximal leg, four cases involved the distal thigh, and two cases involved the lateral knee. The donor site was directly closed in 24 cases, while 15 cases required skin grafting.

The overall complication rate in this study was 20.5% (Table 3). The most common complication was distal tip necrosis. One case of partial flap loss required surgical debridement and skin grafting. There were two cases of donor site hematoma requiring surgical evacuation. In one case, the patient was obese while the other patient was on a continuous heparin infusion due to artificial heart valves. All studies reported favorable outcomes with complete wound healing. Both of our cases achieved complete healing and recovered a full range of motion (Fig. 5).

Postoperative results of both cases. (A) Case 1: postoperative picture at 6 months demonstrating full wound healing. The patient declined dog-ear revision. (B) Case 2: maximal flexion of the knee demonstrated at 5 months postoperatively.

Case 1

A 23-year-old man was referred to us after a traffic accident for coverage of a left knee wound measuring 4 × 8 cm with an exposed patella tendon. A 4 × 12 cm SLGA flap was harvested from the lateral thigh with primary closure of the donor site. The decision was made intraoperatively not to island the flap and a skin bridge was retained adjacent to the pivot point (Fig. 6). The postoperative recovery was uneventful, with complete healing within 1 month.

Original wound and flap design of case 1. (A) Post-debridement wound over the anterior aspect of the knee with a visible patellar tendon. (B) Superior lateral genicular artery (SLGA) flap raised with an isolated perforator and transposed with an intact skin bridge adjacent to the pivot point of the flap. (C) SLGA flap transposed with an intact skin bridge and inset in this position. (D) Final clinical result with a dog-ear located over the location of the pivot point.

Case 2

A 45-year-old man was involved in a traffic accident and sustained a deep 10 × 12 cm wound over the left anterior knee with an exposed patella. After serial debridement, the patient underwent reconstruction of the defect with an SLGA flap measuring 5 × 12 cm. The region of exposed bone was covered with the flap while the remaining wound was skin-grafted (Fig. 7). The donor site was partially closed and the distal portion near the pedicle was skin-grafted to avoid excessive tension. Flap recovery was uneventful. Five months postoperatively, he was noted to have a good range of motion in his knee.

Original wound and flap design of case 2. (A) Post-debridement defect over the anterior aspect of the knee with exposed patellar bone over the superolateral aspect. (B) SLGA flap raised with an isolated perforator at the base of the flap representing the pivot point. (C) SLGA flap islanded and rotated about its pivot point to cover a critical defect of the exposed bone. The remaining portion of the defect and part of the donor site were skin-grafted. (D) Final clinical result.

DISCUSSION

Classically, muscle flaps have been used to cover defects around the knee region. The limitations of these flaps, however, include bulkiness, poor cosmesis, and donor site morbidity [12]. Local random pattern flaps are limited by their size. Free flaps are a good choice, but involve microsurgical expertise and can be technically difficult because of deep recipient vessels [10].

Common fasciocutaneous flaps for knee reconstruction include the reversed anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap and the medial sural artery perforator (MSAP) flap. The downside of the reversed ALT flap is the variability of the vascular pedicle and its bulkiness. The MSAP flap is reliable, with a long pedicle that provides thin fasciocutaneous tissue, but the tedious intramuscular dissection required for mobilization is a disadvantage [16]. In contrast, the perforator of the SLGA is frequently septocutaneous [8]. Moreover, the calf region is often involved in the trauma [17], precluding the use of the MSAP flap.

Flap tip necrosis or delayed healing is the most common complication (15.4%). This is comparable to other fasciocutaneous flaps in lower limb reconstruction, with flap necrosis rates of 13% reported by Yasir et al. [18]. A potential measure to mitigate this issue is to leave a bridge of skin adjacent to the pivot point of the flap as previously described. The downside of this technique is the limitation of movement and the presence of a dog-ear (Figs. 3, 6). The limitation of movement can be offset by designing a longer flap, while a dog-ear can be corrected with simple revision surgery.

If a long flap is required, we suggest assessing the flap with indocyanine green (ICG) to minimize flap tip complications. Using ICG to determine the viability of skin flaps has been gaining popularity, with multiple studies showing its ability to predict clinical outcomes for partial and total skin necrosis [19].

The overall complication rate for the SLGA flap is 20.5%, comparable to the complication rates of other perforator flaps of the leg, which range from 25.8% to 44% [2,20]. No SLGA flaps progressed to complete flap loss. In contrast, the overall free flap failure rates ranged from 4% to 19% [2].

The SLGA flap is a versatile fasciocutaneous flap that can be reliably used for reconstruction of the distal thigh, knee, and proximal third of the leg. It provides sizable soft tissue coverage with minimal donor site morbidity. The anatomy is consistent and dissection is straightforward.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Patient consent

The patients provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of their images.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: V Nallathamby. Data curation: OW Low, TF Loh. Formal analysis: OW Low, H Lee, YL Yap, J Lim, TC Lim, V Nallathamby. Writing - original draft: OW Low. Writing - review & editing: OW Low, V Nallathamby. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.