Median Nerve Compression by the Feeding Vessels of a Large Arteriovenous Malformation in the Axilla

Article information

Arteriovenous (AV) malformations are fast-flowing vascular anomalies that bypass the capillary vessels and provide a supraphysiologic shunting path between arteries and veins. Such lesions most commonly occur in the head and neck area, with approximately 15% of cases occurring in the extremities [1]. Although various surgical treatments exist for AV malformations, curative resections are difficult due to the unclear surgical margins and propensity for bleeding. Moreover, recurrence is common. AV malformations have rarely been reported to cause nerve compression syndrome, and the feeding artery has never been reported to cause median nerve entrapment. In this case report, we present the successful resection of a right axillary AV malformation in a patient with median nerve entrapment symptoms.

A 37-year-old male patient presented with a two-year history of a slowly growing mass in the right axilla and anterior chest wall (Fig. 1). He reported no significant medical history or familial medical history. This growth was associated with intermittent episodes of neurogenic pain that radiated from the right forearm to the fingers. The lesion was tender and erythematous with a palpable thrill and bruit. The patient also complained of pain with abduction and external rotation of the right shoulder joint. No muscle weakness was noted, so a preoperative electromyogram was not conducted.

Preoperative photograph. A 37-year-old man presented with subcutaneous masses consistent with large arteriovenous malformations of the right axilla and anterior chest.

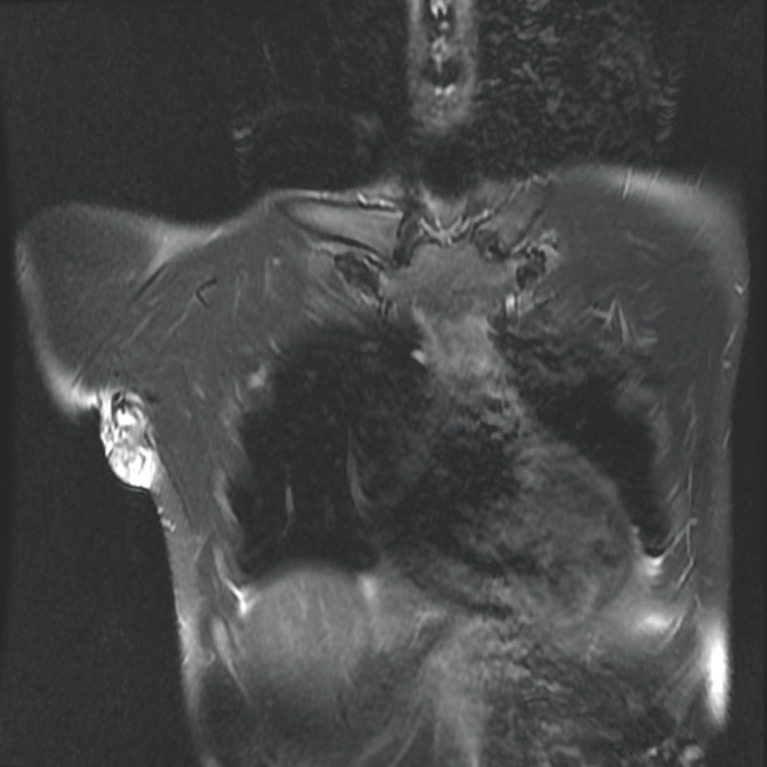

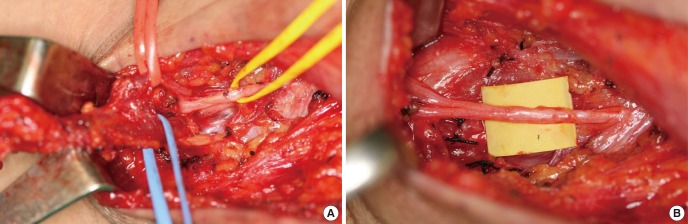

Preoperative imaging included Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. The lesion was composed of two tortuous vascular structures connected with vessels and supplied by branches of the right axillary artery and internal mammary artery, respectively. The lesion drained into their venae comitantes and showed heterogeneous enhancement on a contrast-enhanced MRI scan (Fig. 2). The resection was performed under general anesthesia. The lesion was approached via an incision extending from the right axilla to the anterior chest. The normal tissue was dissected away from the lesion, with special care taken to protect the neurovascular structures. Two arteries rose from the axillary artery and internal mammary artery and fed into two separate masses. The median nerve was trapped between the axillary artery and vein (Fig. 3). However, the nerve had not undergone pathologic changes and was released from the fibrous attachment. The axillary portion of the lesion measured 9×6×3 cm, and the anterior chest portion measured 10×9×5 cm. Both portions were excised with satisfactory hemostasis. The subcutaneous tissue and skin were closed primarily.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging with enhancement. Coronal view of a T2-weighted fat-suppressed image.

Intraoperative photographs. (A) The median nerve (yellow loop) was trapped between the right axillary artery (red loop) and vein (blue loop). (B) The median nerve was freed from the feeding artery, the feeding vein, and the associated fibrous tissue.

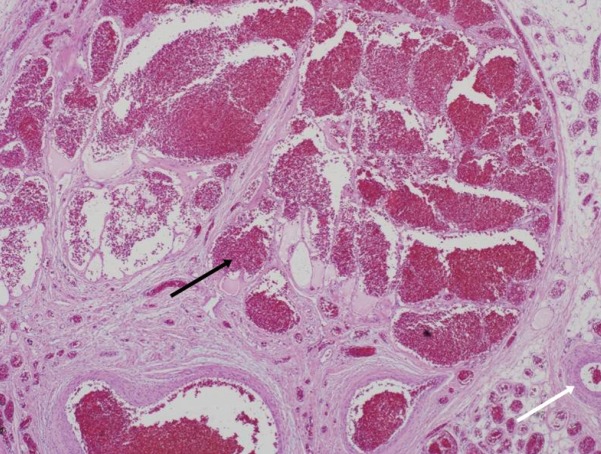

Histologic examination of the surgical specimen showed that the mass contained a high density of feeding arteries and draining veins within a fibrofatty matrix of dense collagen and reticular fiber. The tortuous arteries contained fragmented elastic lamina and were surrounded by thick-walled veins with hypertensive intimal changes. These observations confirmed the diagnosis of AV malformation (Fig. 4).

Histology of the surgical specimen. The mass in the right axilla contained a high density of feeding arteries (white arrow) and draining veins (black arrow) within a fibrofatty matrix of dense collagen and reticular fiber (H&E, ×40).

The patient recovered without any complications, and was discharged home on the ninth day after the operation. The intermittent neurologic pain and paresthesia did not return, and the pain associated with the shoulder joint had fully resolved. The patient did not experience hand numbness after the operation. The masses had not recurred at a three-year follow-up examination, and the patient did not experience any relapse of neuralgic pain and muscle weakness.

The symptoms of AV malformation can vary, including warmth, pain, paresthesia, hyperhidrosis, and/or compressive neuropathy, depending on the size and location of the lesion. In our case, pulsatile masses were observed in the right axilla and anterior chest wall. The masses were tender and warm with a palpable thrill and bruit. The overlying skin followed the undulating contour of deeper tissue but was without any ulceration or necrosis. Abduction and external rotation of the humerus was limited secondary to pain. This clinical presentation was consistent with a stage II AV malformation according to the Schobinger clinical staging system [1].

The median nerve is a terminal branch of the medial and lateral cord from the brachial plexus, and travels along the medial side of the brachial artery. This peripheral nerve does not innervate any of the muscles above the elbow and is responsible for most of the flexor muscles in the forearm. In the hand, the nerve stimulates the first and second lumbrical muscles and provides sensation to the medial two-thirds of the palmar surface [2]. Depending on the level, medial nerve entrapment can result in carpal tunnel syndrome (wrist), anterior interosseous syndrome (forearm), or pronator syndrome (elbow). In our case, the median nerve was trapped at the axilla between the axillary artery and vein. While the patient did present with intermittent neuralgia, no motor weakness was observed prior to the operation. These episodes were most likely due to transient compression of the nerve between the feeding artery and vein, and the intraoperative findings were consistent with the clinical presentation, as the trapped nerve was healthy, with no pathologic changes.

Strategies for treating AV malformation include sclerotherapy, embolization, surgical resection, or a combination thereof [345]. Sclerotherapy is the injection of a sclerosing agent such as ethanol or bleomycin directly into the lesion to close the shunt. Embolization is similar to sclerotherapy in principle and form, but accomplishes the same goal of closing the shunt by direct obstruction of the shunting vessels using embolizing agents. However, embolization is usually followed by the development of collateral vessels and can increase the size of the lesion as well as worsening pre-existing symptoms, such as skin ulceration. Neither sclerotherapy nor embolization requires a surgical incision, but these procedures are both highly dependent on the interventional radiologist performing the procedure. Surgical excision is effective, but may result in significant intraoperative bleeding and a large soft tissue defect. In our case, the preoperative MRI was helpful in identifying a surgically viable margin. Preoperative embolization was not necessary, and bleeding was minimal during the operation. Surgical excision of the lesion and mobilization of the median nerve were associated with cessation of the neuralgic symptoms as well as the clinical symptoms related to the AV malformation itself.

This case demonstrates that compressive median neuropathy can be caused by the feeding vessel of an AV malformation in the axilla. Prompt excision of the lesion can prevent neurologic sequelae caused by a compressive vascular lesion of this type.

Notes

This article was presented at the 70th Congress of the Korean Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons on November 9-11, 2012 in Seoul, Korea.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.