Scar Revision Surgery: The Patient's Perspective

Article information

Abstract

Background

Insufficient satisfaction outcome literature exists to assist consultations for scar revision surgery; such outcomes should reflect the patient's perspective. The aim of this study was to prospectively investigate scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes, according to specified patient-selection criteria.

Methods

Patients (250) were randomly selected for telephone contacting regarding scar revisions undertaken between 2007-2011. Visual analogue scores were obtained for scars pre- and post-revision surgery. Surgery selection criteria were; 'presence' of sufficient time for scar maturation prior to revision, technical issues during or wound complications from the initial procedure that contributed to poor scarring, and 'absence' of site-specific or patient factors that negatively influence outcomes. Patient demographics, scar pathogenesis (elective vs. trauma), underlying issue (functional/symptomatic vs. cosmetic) and revision surgery details were also collected with the added use of a real-time, hospital database.

Results

Telephone contacting was achieved for 211 patients (214 scar revisions). Satisfaction outcomes were '2% worse, 16% no change, and 82% better'; a distribution maintained between body sites and despite whether surgery was functional/symptomatic vs. cosmetic. Better outcomes were reported by patients who sustained traumatic scars vs. those who sustained scars by elective procedures (91.80% vs. 77.78%, P=0.016) and by females vs. males (85.52% vs. 75.36%, P<0.05), particularly in the elective group where males (36.17%) were more likely to report no change or worse outcomes versus females (16.04%) (P<0.01).

Conclusions

Successful scar revision outcomes may be achieved using careful patient selection. This study provides useful information for referring general practitioners, and patient-surgeon consultations, when planning scar revision.

INTRODUCTION

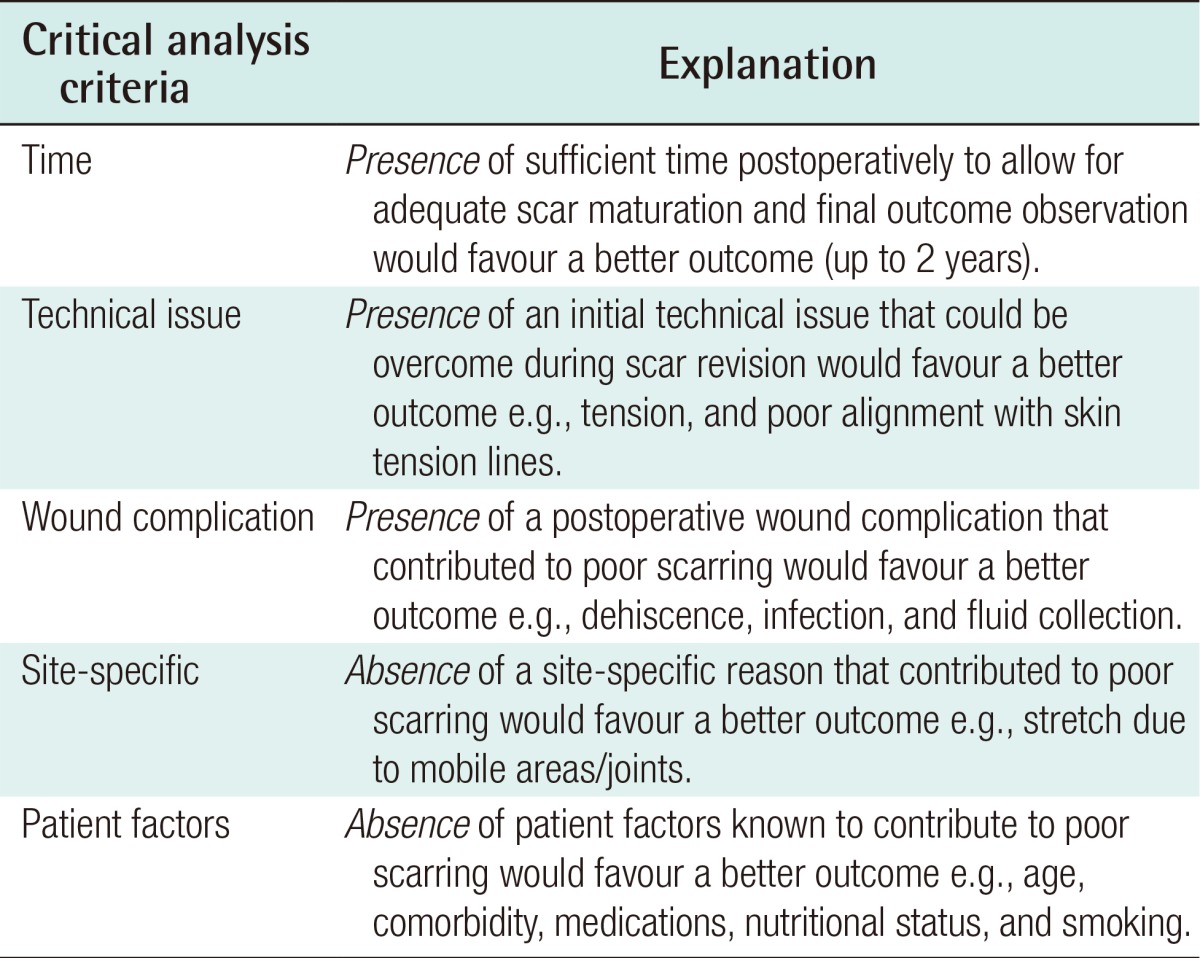

The ideal scar should be imperceptible, narrow, flat, homogenous, with no surrounding distortion or functional disturbance [12]. Factors affecting scar revision surgery may be classified as patient factors (age, comorbidity, medications, nutritional status, and smoking), local factors (blood supply, fluid collection, infection, and radiotherapy) or technical factors (technique, over mobile sites e.g., and joints) [12]. Tethered scars are a common surgical problem that may produce contour defects, lead to functional restriction or growth abnormalities [3]. To address such issues, many scar revision techniques have been described including excision and direct closure, dermis enhancement (dermal tube, double-breasting, and dermal graft), local flaps (Z-plasty, W-plasty, and other variants), fillers and tissue expansion [456789]. However, regardless of the chosen surgical technique, unsatisfactory outcomes may still occur due to inadequate pre-revision critical analysis of the nature by which the scar was formed; our recommended critical analysis criteria are outlined (Table 1) [210].

While a variety of scar assessment tools exist including the visual analogue scale (VAS), Vancouver burn scar assessment score and the clinical scar assessment scale, there is a shortfall of adequate literature data to assist the patient and surgeon in predicting scar revision outcomes [41112]. Such data should primarily reflect the patient's perspective and recognise the natural history of scar maturation; it has been shown that when assessed at 6 and 18 months, patients recognise scar appearance improvements during maturation, a process that may take up to 2 years [13].

The primary aim of this study was to present patient satisfaction criteria, from 5 years of clinical practice at a large tertiary referral centre (Table 1). These departmental criteria reflect well recognised principles that directly apply to optimising patient selection for scar revision surgery (Table 1) [1214151617]. They consider the 'presence' of sufficient time for scar maturation prior to revision, technical issues during or wound complications from the initial procedure that contributed to poor scarring, and 'absence' of site-specific or patient factors that negatively influence outcomes (Table 1) [1214151617]. Further study aims included studying the differences between sex, pathogenesis (sustained in a traumatic vs. elective setting), underlying issue (functional/symptomatic vs. cosmetic), and body sites. The null hypotheses were that no differences would be demonstrated.

METHODS

After clinical governance registration, patients were prospectively contacted by telephone, using a standardised protocol, to provide VAS satisfaction ratings (0-10; 0, extremely bad scar; 5, moderate scar; 10, excellent scar) of their scar, pre- and post-revision surgery. Patients (250/573) were randomly selected to ensure an adequate sample size for each of the following scar pathogenesis groups; traumatic vs. elective. The inclusion criterion was scar revision surgery undertaken between 2007-2011 to facilitate a minimum 2 years follow-up per patient. The exclusion criteria were scar revision operations for dog ears and patients who were not prospectively contactable. Further data were collected including patient demographics (age, sex), underlying issue (functional/symptomatic vs. cosmetic) and details of revision surgery (date, body site) were additionally cross referenced with a real-time secure plastic surgery electronic hospital database and electronic patient records. Parametric continuous data were analysed by t-tests and discrete data were analysed by chi-squared tests using SPSS ver. 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

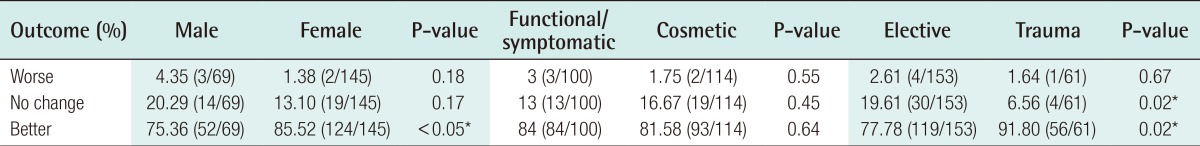

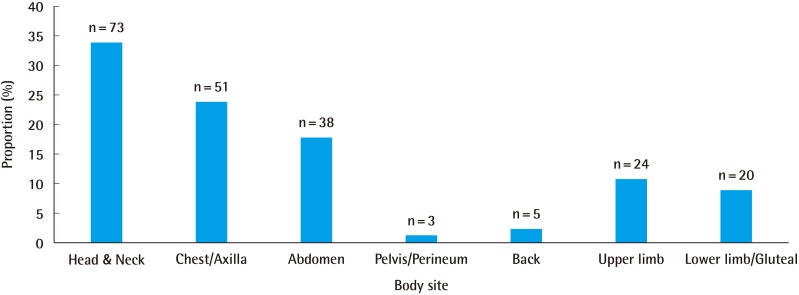

Prospective telephone contacting was achieved for 211 patients (male [M]=68 /female [F]=143) who underwent 214 operations over the study period, with the proportion of operations performed by body site illustrated (Fig. 1). A minimum 2 years follow-up period was achieved for 100% of patient procedures (214/214). Overall scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes were; 2.34% (5/214) worse, 15.89% (34/214) no change, 81.78% (175/214) better, distributions that remained similar regardless of body site (Fig. 2) or whether the underlying issue was functional/symptomatic vs. cosmetic (Table 2). In all cases where scar revision was performed for cosmetic reasons, the initial scarring was sustained in non-cosmetic procedures in patients without body dysmorphic disorder or related confounding diagnoses. When stratified by sex, females (85.52%) were more likely than males (75.36%) to report better satisfaction outcomes, hence males (24.45%) were more likely to report worse or no change in outcome vs. females (14.48%) (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Proportion (%) and numbers of scar revision procedures (n=214) undertaken by body site

The proportion of procedures performed by body site were; head and neck (34.1%, n=73), chest and axilla (23.8%, n=51), abdomen (17.8%, n=38), pelvis and perineum (1.4%, n=3), back (2.3%, n=2), upper limb (11.2%, n=24), lower limb and gluteal region (9.3%, n=20).

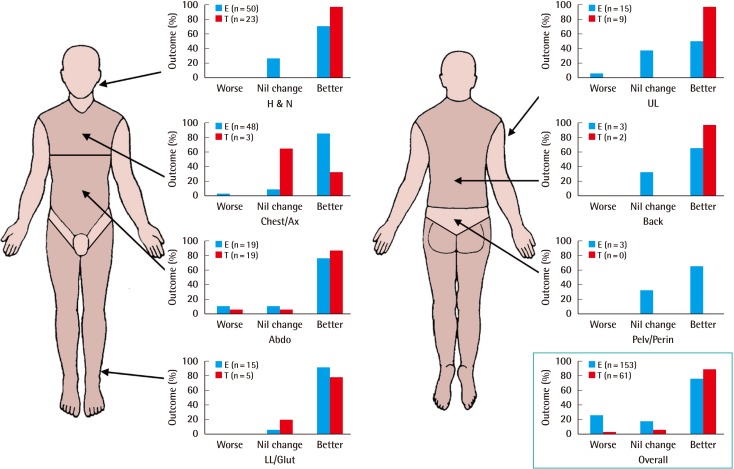

Scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes (%) by body site

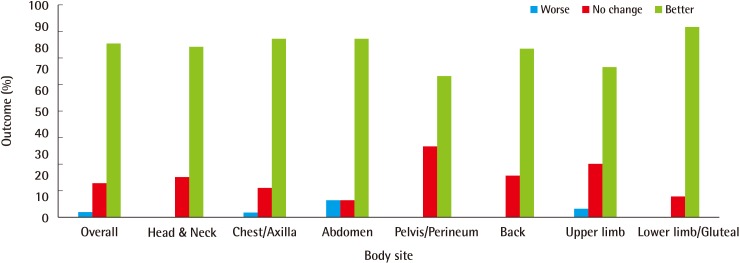

Overall scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes were as follows; 2.34% (5/214) worse, 15.89% (34/214) no change, 81.78% (175/214) better, distributions that remained similar regardless of body site.

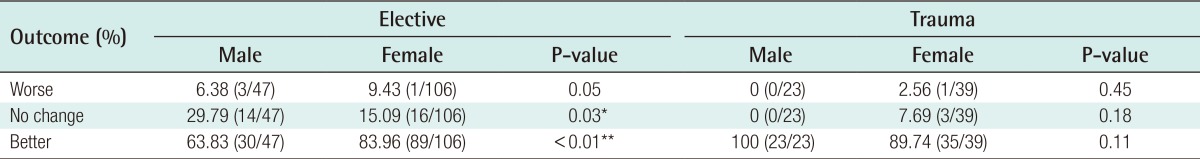

With respect to pathogenesis, 153 procedures were performed for 151 (M=47/F=104) patients (age 44±1 years) whose scars were sustained in the elective setting, while 61 procedures were performed for 60 (M=21/F=39) patients (age 40±2 years) whose scars were sustained by trauma; both groups were age-matched (P=0.14). Patients who sustained scars from trauma (91.80%) were more likely to report better scar revision satisfaction outcomes than those who sustained scars in the elective setting (77.78%) (P=0.016), hence patients who sustained scars in the elective setting (22.22%) were more likely to report no change or worse outcomes than those who sustained scars from trauma (8.20%) (P=0.016). Furthermore, patients who sustained scars in the elective setting (19.61%) were more likely to report no change in outcome compared to those who sustained scars from trauma (6.56%) (P=0.02) (Table 2).

Pathogenesis sub-analysis by body site (Fig. 3) indicated similar scar revision outcome distributions as those previously illustrated (Fig. 2). However, due to relatively small sub-group sample sizes, only the head and neck region was further analysed, with patients who sustained scars from trauma (100%) more likely to report better satisfaction outcomes than those who sustained scars in the elective setting (72%) (P<0.01). Pathogenesis sub-analysis by sex indicated that females (83.96%) who sustained scars in the elective setting were more likely to report better outcomes than males (63.83%) (P<0.01), hence males (36.17%) were more likely to report no change or worse outcomes versus females (16.04%) (P<0.01) (Table 2). Furthermore, in the elective setting males (29.79%) were more likely than females (15.09%) to report no change in outcome (P= 0.03) (Table 2). No inter-sex differences were demonstrated in the traumatic setting (Table 2).

Scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes for scars pathogenesis (elective vs. trauma), stratified by body site

Patients who sustained scars from trauma (91.80%) were more likely to report better scar revision satisfaction outcomes than those who sustained scars in the elective setting (77.78%) (P=0.016), hence patients who sustained scars in the elective setting (22.22%) were more likely to report no change or worse outcomes than those who sustained scars from trauma (8.20%) (P=0.016). Patients who sustained scars in the elective setting (19.61%) were more likely to report no change in outcome compared to those who sustained scars from trauma (6.56%) (P=0.02). Worse scar revision outcomes were similar for those sustained in the elective setting vs. trauma (2.61% vs. 1.64%, P=0.67). These distributions remained similar regardless of body site. E (blue), patient group with scars sustained from elective surgery; T (red), patient group with scars sustained from trauma; H&N, head & neck; Ax, axilla; Abdo, abdomen; LL/Glut, lower limb/gluteal; UL, upper limb; Pelv/Perin, pelvis/perineum.

DISCUSSION

Patient-reported overall scar revision satisfaction outcomes generally followed a 2% worse, 16% no change, and 82% better distribution, figures that were maintained between body sites; the 3 most common body sites were head and neck (34%), chest/axilla (24%) and abdomen (18%) (Fig. 2). While scar revision has been associated with high patient satisfaction in the past, few studies have examined this objectively and from the patient's perspective [18]. Examples of such studies include an analysis of 18 ears in 13 patients, 84.62% reported good scar revision outcomes following intralesional excision of persistent hypertrophic or keloid scars, with the remaining 2 patients reporting acceptable outcomes (mean follow-up, 3.6 years); such findings are in-keeping with our results (Fig. 2) [19].

Another study of 32 patients, prospectively followed-up at 12 months after tethered scar revision using a dermal tube method, indicated 100% improvement outcomes from the patient's perspective using a VAS (0-2). Again, a high proportion of high satisfaction outcomes were reported; although higher than our findings, we present data from a broader spectrum of indications, with a larger sample size than previous studies, and over a minimum 2 years follow-up period to allow for scar maturation [4].

Not only were scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes similar regardless of whether surgical indications were for functional/symptomatic or cosmetic reasons, this distribution paralleled our previously discussed overall outcomes. The consistency between these findings provides supportive evidence for our critical analysis criteria for scar revision patient selection (Table 1); using these selection criteria should therefore facilitate more predictable outcome discussions, from the patient's perspective, during preoperative consultations.

The fact that patients who sustained scars from trauma were more likely to report better scar revision outcomes than those who sustained scars in the elective setting, and that those who sustained elective procedure scars were more likely to report no change or worse outcomes than those who sustained traumatic scars, is interesting (Table 2). Traumatic conditions are likely less favourable for initial good scar formation e.g., due to contamination, skin loss or because traumatic lacerations often do not respect the orientation of skin tension lines. Hence, it is probable that patients who sustain scars from trauma, are more likely to occupy more critical analysis patient selection criteria, favouring better scar revision outcomes (Table 1). Furthermore, such patients may also have lower expectations versus those who sustain scars in the elective setting, thus influencing better reported outcomes following scar revision surgery.

Of further interest, females (85.52%) were more likely to report better outcomes versus males (75.36%) (P<0.05), a trend that was sustained for scars sustained in the elective setting (83.96% vs. 63.83%, P<0.01) but not during trauma; hence in the elective setting only, male patients were more likely to report worse or no change in outcome versus females (Tables 2, 3). Furthermore in the elective setting only, male patients were more likely to report no change in outcome vs. females (Table 3). Psychological observations of patients seeking elective cosmetic procedures have been reported in the literature since the 1940s [20]. At this time surgeons were warned of the psychopathology of male patients and the 'insatiable' surgery patient seeking multiple elective cosmetic procedures in pursuit of the perfect face; despite concerns regarding the psychological state of patients, procedures were rarely excluded and positive psychiatric outcomes reported [21]. Pre-selection criteria have evolved dramatically since this time, with emphasis on recognised psychological conditions e.g. body dysmorphic disorder and an increase in male uptake, in order to improve patient selection for elective cosmetic procedures [222324]. These studies relate to our findings as they support the idea of inter-sex differences that may vary across a broad range of elective cosmetic procedures; our data support the concept of possible personality differences between females and potentially hyper-aware males, regarding the cosmetic appearance of their scars. Higher expectation precipitated by such personality traits could negatively influence the patient's opinion of their scar revision outcome. This is particularly so in the elective setting as patient expectation may be significantly higher.

Scar revision patient satisfaction outcomes for male and female patients who sustained scars in either an elective or traumatic setting

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that successful scar revision surgery outcomes may be achieved using careful patient selection. The outlined patient selection criteria in this study directly apply to optimising patient selection for scar revision surgery; 'presence' of sufficient time for scar maturation prior to revision, technical issues during or wound complications from the initial procedure that contributed to poor scarring, and 'absence' of site-specific or patient factors that negatively influence outcomes (Table 1) [1214151617]. Overall patient satisfaction outcomes were reported as; 2% worse, 16% no change and 82% better (Fig. 2). These figures were consistent between body sites and better outcomes were reported for revisions undertaken in scars sustained from trauma as opposed to elective procedures (Table 3, Figs. 2, 3). Overall, females reported better scar revision outcomes vs. males, particularly with scars sustained in the elective scenario where males were more likely to report worse/no change in outcome (Tables 2, 3). These evidence-based findings provide useful information for the referring general practitioner and patient-surgeon consultation when planning scar revision.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.