Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia Presenting as Rapidly Growing Bilateral Breast Enlargement Refractory to Surgical Excision

Article information

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is a benign proliferative mesenchymal lesion of the breast. PASH presents as a palpable or mammographically detectable mass or is an incidental microscopic finding in up to 23% of breast biopsies. Its pathogenesis is unclear but may involve hormonal factors, as recently postulated. Its clinical, cytological, and radiological characteristics resemble those of other benign tumors, including low-grade angiosarcomas and phyllodes tumors. Because of its uncertain pathogenesis, PASH is usually treated via surgical excision, with post-excision recurrence rates ranging from 7% to 22% [1]. Although several cases of PASH have been recently reported, cases of PASH involving large, rapidly growing lesions refractory to surgical incision are rare [2]. In this study, we report our experience with a case of PASH that presented as rapidly growing bilateral breast enlargement refractory to surgical excision. We also review the pertinent literature, including the clinical and histopathological features, pathogenesis, imaging findings, treatment, and prognosis of PASH.

A 41-year-old woman presented at the general surgery department of our hospital with a two-month history of painful swelling of the breasts (Fig. 1). She had been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus 15 years previously and was premenopausal. Her family had no history of breast disease. Ultrasonography (USG) performed during a breast examination a month before she visited our hospital did not reveal any specific lesions in her breasts.

Preoperative photograph. A 41-year-old woman presented with swelling of both breasts. The volumes of the right and left breast were 1,115 mL and 980 mL, respectively, as measured using the casting method.

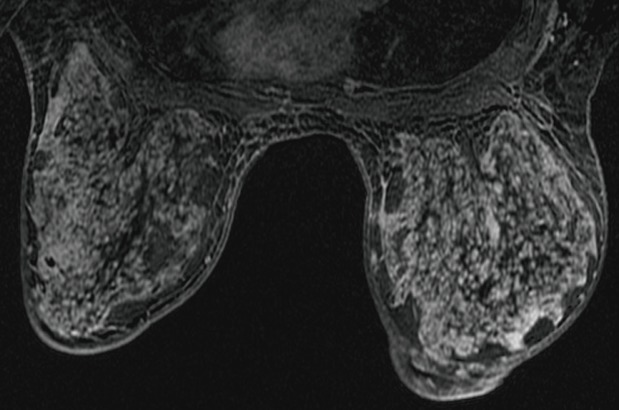

Upon presentation at our hospital, both breasts were excessively enlarged, with erythematous changes in the periareolar skin. However, neither a discrete mass nor the axillary lymph nodes were palpable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, performed to rule out prolactinoma, showed a normal pituitary gland. Breast USG revealed bilateral skin and breast parenchymal thickening, diffuse heterogeneous hypoechoic parenchyma with ill-defined cystic lesions, hyperechoic subcutaneous fat, and increased vascularity of the superficial breast tissue and the subcutaneous layer. Breast MRI revealed a diffuse, homogenous, persistent enhancement (Fig. 2). Because of the persistent hypertrophy of both breasts, a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the presence of bilateral breast lesions, and mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration was diagnosed.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both breasts. MRI shows diffuse homogenous persistent enhancement in a post-contrast-subtracted T1-weighted image.

Although painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs alleviated the pain in her breasts, the patient wanted to have her enlarged breasts reduced in size. Because specific breast lesions were absent, the patient was referred to the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery for management of her enlarged breasts. Preoperatively, the volumes of her right and left breasts were 1,115 mL and 980 mL, respectively, as determined using the casting method.

Bilateral reduction mammoplasty was performed using the superomedial pedicle inverted-T technique. The patient healed without complications. Histological examination of the excised mass revealed periductal edematous changes, mild lymphocytic infiltration, and the presence of collagen and fibroblasts in the stroma, and PASH was diagnosed.

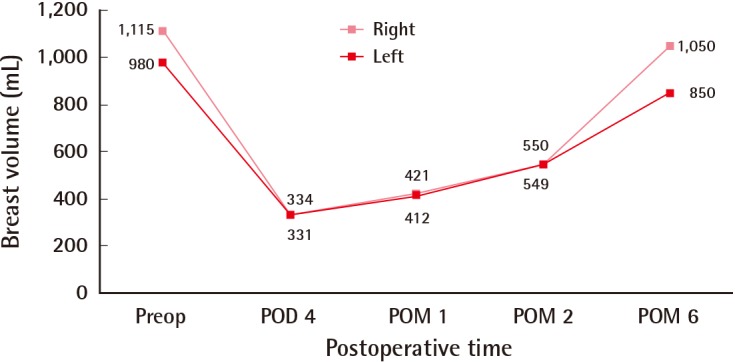

The immediate postoperative breast volumes were 334 mL (right) and 331 mL (left), and the patient was satisfied with these results. The patient's breasts increased in volume during the six months after the surgery. Six months after the operation, the breast volumes were 1,050 mL (right) and 850 mL (left), which were similar to the preoperative sizes of her breasts (Figs. 3, 4). Other than breast enlargement, the patient did not experience any complications such as pain or discharge. She chose not to undergo additional surgical treatment and was lost to follow-up.

Serial postoperative outcomes. (A) One-month postoperative view. (B) Six-month postoperative view. Breast enlargement over time is seen.

Change in breast volumes. A comparison of the preoperative and postoperative breast volumes (mL), showing postoperative increases in both breasts. Preop, preoperative; POD, postoperative day; POM, postoperative month.

PASH was first described by Vuitch et al. in 1986 [3]. This histological study showed that it consists of mammary stromal proliferation. The term "pseudoangiomatous" described this histological feature, which resembles angiomatous proliferation. The authors emphasized the significance of distinguishing PASH, which is benign, from other vascular tumors. The age range of patients with PASH is 14–67 years, although most present before menopause. PASH is frequently an incidental histological finding during breast examinations performed to detect benign or malignant lesions. Its etiology and pathogenesis remain unknown. Endogenous and exogenous hormones may be important for PASH development, because PASH occurs primarily in premenopausal women [1].

PASH commonly appears as a circumscribed, non-calcified mass or as a focal asymmetry in mammograms and as a hypoechoic, oval, circumscribed mass, usually without a cystic component, in USG [4]. Core-needle biopsies can be used to accurately diagnose PASH [2]. Microscopically, PASH consists of a network of vascular endothelial-like spindle cells that form vessel-like slits in the stroma; the slits are not bona fide vessels covered with endothelial cells, but vacant spaces covered with myofibroblasts [3].

For local control, many authors recommend treating PASH by completely excising the mass, with sufficient safety margins and regular follow-ups because of the uncertain pathogenesis and progression of PASH. When the lesions are diffuse, mastectomy with breast reconstruction may be an alternative approach. Medical treatment requires the administration of hormones such as tamoxifen for small lesions [1]. The recurrence rate of PASH ranges from 0% to 22%. PASH is a benign breast lesion and is not considered premalignant, but does exhibit a tendency for growth over time. Most patients with PASH have a good prognosis [5].

Although PASH is not an uncommon benign lesion of the breast, only a few cases of tumorous PASH causing rapidly growing breast enlargement have been reported [2]. In our case, a punch biopsy was performed preoperatively and revealed mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, suggesting that the lesions were not PASH. Due to the absence of specific lesions, we were unable to ensure adequate safety margins during the reduction mammoplasty, and the lesions recurred postoperatively. We recommended mastectomy after the recurrence of the breast enlargement, but the patient refused additional surgery.

In conclusion, plastic surgeons should include PASH in their differential diagnosis of rapidly growing enlarged breasts in order to ensure proper treatment. Knowing the complete and exact medical history of the patient is necessary for correctly diagnosing the disease. We recommend performing microscopic examinations in all reduction mammoplasty patients after the excision, if possible.

Notes

This article was presented at the Fourth Research and Reconstructive Forum of the Korean Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons on April 3−4, 2014 in Pusan, Korea.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.