Post-Traumatic Cutaneous Meningioma

Article information

Neurological tumors pose considerable challenges from the point of view of diagnosis and therapeutic management. Their location makes them difficult to study and to approach surgically, especially when they are located within the skull or in the spinal canal. In contrast, skin tumors tend to be easier to identify and to approach surgically. We report the case of a patient with a neurological tumor that behaved like a skin tumor: a cutaneous meningioma secondary to a skull fracture.

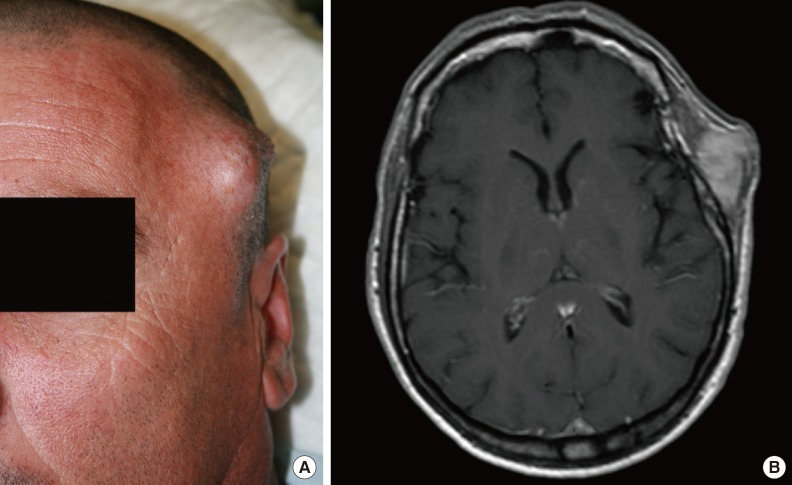

A 51-year-old male with a history of a motorcycle accident that caused a skull fracture in the left temporoparietal region 15 years previously was referred to our outpatient clinic. He presented with a tumor that had increased in size over the previous four years in that area (Fig. 1A). A biopsy of the tumor revealed a cutaneous meningioma. An imaging study using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed encephalomalacia with discrete foci of reactive gliosis in the frontal, medium, and temporal left gyrus. A left temporoparietal fracture, which may have been old, was identified, as well as a 24×38×39-mm mass of extracranial soft tissue reaching the skin (Fig. 1B). No infiltrations of the underlying bone or intracranial components were observed.

(A) Skin tumor in the temporoparietal region. (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. The tumor is hyperintense relative to the gray matter.

A bloc resection was performed, including a skin segment infiltrated by the tumor, the aponeurotic galea, the temporal muscle, and cranial periosteum, without affecting the bone (Fig. 2A). A paresis of the frontal branch of the left facial nerve was identified during follow-up in our outpatient clinic. An electrophysiological study was requested two months after the surgery, and a partial axonal injury was observed in the frontal branch of the left facial nerve, showing signs of reinnervation.

(A) Bloc resection of the tumor in the left parietal region. A skin segment was included due to infiltration. (B) Seven months after the tumor excision.

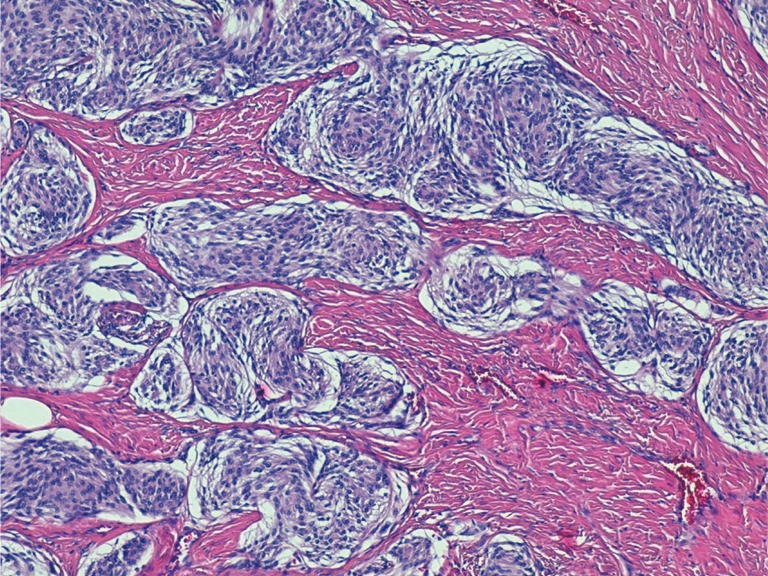

A histological study revealed multiple nests of elongated cells exhibiting a swirling pattern and with little nuclear pleomorphism. The tumor displayed an infiltrative character, infiltrating adipose tissue and muscle tissue (Fig. 3). It was located less than 1 mm from the deep surgical margin. An immunohistochemical study was performed, and the tumor cells tested positive for vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and progesterone. MIB-1 proliferation index was approximately 3% of the total cell volume.

Histological study (H&E, ×100). Multiple nests of elongated cells are found, with a swirling pattern and with little nuclear pleomorphism.

Seven months after surgery, the patient remains asymptomatic and has regained full mobility of the left frontal muscle (Fig. 2B).

Meningiomas are the most common tumors of neurological origin in adults, accounting for 15%–30% of all intracranial neoplasms [1]. They most commonly present intracranially. Extracranial meningiomas represent 1%–2% of all meningiomas [2]. The ectopic location of these tumors outside the central nervous system can result from the direct extension of intracranial tumors through the foramina, metastatic meningiomas, or meningiomas of primary origin.

Within primary ectopic meningiomas, cutaneous meningiomas are a rare anatomical variant. In 1974, Lopez et al. [3] classified cutaneous meningiomas into three groups The first group (type I) is congenital. It presents at birth and usually appears on the scalp and paravertebral skin. It is caused by ectopic arachnoid cells trapped in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue during embryonic development. The second group (type II) consists of meningiomas extending to the skin through contiguity. They tend to appear in areas surrounding the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. It has been hypothesized that they are formed by the remnants of arachnoid cells that extend through the cranial and spinal nerves [1]. The third group (type III) comprises meningiomas that have spread to the skin from intracranial tumors, traumatic defects, or surgical procedures. These tumors are more common in adults.

It has been postulated that post-traumatic cutaneous meningiomas appear due to the interruption of the craniofacial bone structures and the underlying meninges, leading to meningeal tissue migration within the dermis and resulting in a tumor some years later [2]. In our case, we observed a cutaneous meningioma belonging to type III according to Lopez's classification. Type III tumors are uncommon, although some cases of post-traumatic cutaneous meningioma have been reported in the literature [245].

Although the first group is composed of congenital tumors, they generally are not diagnosed until some years have passed. The mean age for the diagnosis of tumors belonging to the second group is 48 years, and 54 years for type III. The female-to-male ratio is 4:5. Pregnancy has been associated with tumor growth, in relation to baseline hormonal disorders.

In most cases, these tumors appear as firm subcutaneous nodules. They are usually painless, but some cases have been reported in which the patient felt local pain. They can cause bone erosion and cystic cavities. Type II tumors can produce cranial nerve disorders.

The preferred imaging modality for these tumors is MRI, in which these tumors appear isointense relative to the gray matter on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images [2].

The treatment of choice is surgical resection. The prognosis depends on the type of tumor. Type I tumors have a good prognosis after surgical resection, and cases of recurrence have not been documented. Type II and III tumors have less favorable prognoses, especially type III tumors with intracranial involvement. In our case, the patient remains free of signs of recurrence seven months after surgery.

Therapies using vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor inhibitors are currently under investigation. In cases where complete resection is not possible, radiotherapy may be indicated.

The histological study of these tumors shows spindle-shaped cells with round nuclei arranged in small clusters. Immunohistochemical assays are positive for vimentin and epithelial membrane antigen, and negative for cytokeratin, S-100 protein, CD31, CD34, and actin [1].

In conclusion, cutaneous meningioma is a rare neurological tumor that presents as a skin tumor. This kind of tumor must be considered in patients with previous craniofacial fractures. The diagnosis requires an initial imaging study to confirm the intracranial or extracranial origin of the tumor. For this reason, preoperative MRI helps ensure that complications during the surgery are avoided.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.