Informed Consent as a Litigation Strategy in the Field of Aesthetic Surgery: An Analysis Based on Court Precedents

Article information

Abstract

Background

In an increasing number of lawsuits doctors lose, despite providing preoperative patient education, because of failure to prove informed consent. We analyzed judicial precedents associated with insufficient informed consent to identify judicial factors and trends related to aesthetic surgery medical litigation.

Methods

We collected data from civil trials between 1995 and 2015 that were related to aesthetic surgery and resulted in findings of insufficient informed consent. Based on these data, we analyzed the lawsuits, including the distribution of surgeries, dissatisfactions, litigation expenses, and relationship to informed consent.

Results

Cases were found involving the following types of surgery: facial rejuvenation (38 cases), facial contouring surgery (27 cases), mammoplasty (16 cases), blepharoplasty (29 cases), rhinoplasty (21 cases), body-contouring surgery (15 cases), and breast reconstruction (2 cases). Common reasons for postoperative dissatisfaction were deformities (22%), scars (17%), asymmetry (14%), and infections (6%). Most of the malpractice lawsuits occurred in Seoul (population 10 million people; 54% of total plastic surgeons) and in primary-level local clinics (113 cases, 82.5%). In cases in which only invalid informed consent was recognized, the average amount of consolation money was KRW 9,107,143 (USD 8438). In cases in which both violation of non-malfeasance and invalid informed consent were recognized, the average amount of consolation money was KRW 12,741,857 (USD 11,806), corresponding to 38.6% of the amount of the judgment.

Conclusions

Surgeons should pay special attention to obtaining informed consent, because it is a double-edged sword; it has clinical purposes for doctors and patients but may also be a litigation strategy for lawyers.

INTRODUCTION

Patient rights have gradually expanded along with the development of cutting-edge medical technology in South Korea. According to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures, in 2014, there were 2,054 plastic surgeons and 980,313 surgical and non-surgical procedures performed in South Korea, which corresponds to the fourth-highest quantity of procedures worldwide. However, South Korea ranks first in the number of plastic surgeons and procedures per capita [1]. With significant growth in the aesthetic surgery market, intense competition among medical professionals has led to increased and exaggerated advertisements, patient solicitations, and operations performed without adequate patient selection. In addition, the number of medical lawsuits has also increased with the number of procedures performed in this severely competitive environment.

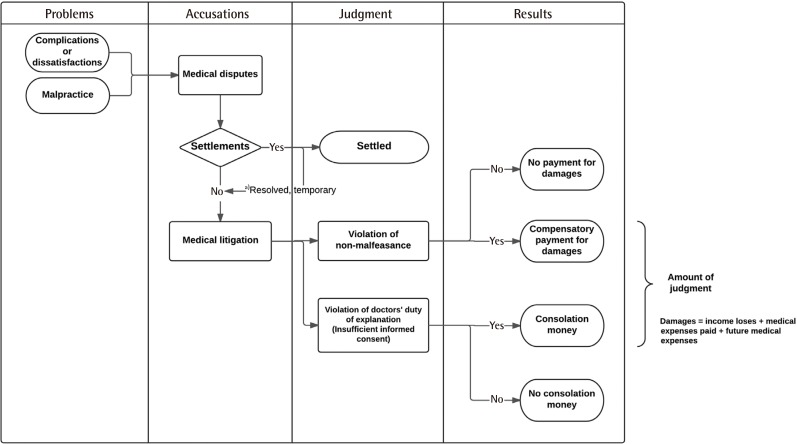

Medical litigation in South Korea

When a patient files a medical lawsuit, it is classified as a damage compensation lawsuit in the civil courts of South Korea. Unlike the US court system, juries do not evaluate cases in civil court in South Korea; instead, a judge determines the outcome. All medical litigation relies on 2 core arguments: violation of the doctor's duty of non-malfeasance and violation of the doctor's duty of explanation (i.e., insufficient informed consent) (Fig. 1).

The medical litigation workflow in South Korea

Settlements include a free-of-charge compensatory procedure or operation and/or compensation money.

a)Resolved, temporary: The patient may consider the matter settled at first, but the remaining dissatisfaction leads him or her to reinitiate the medical dispute. This usually leads to medical litigation.

Violation of the doctor's duty of non-malfeasance means that an instance of malpractice occurred during the procedure, as determined based on testimony from expert counsel. Similarly to the US court system, the elements that must be proven to make a successful claim are (1) the contractual duty between doctor and patient, (2) breach of this duty due to failure to comply with professional standards, (3) a causal relationship between the breach of duty and injury to the patient, and (4) the existence of damage resulting from the injury [2345]. In South Korea, the patient must convince the judge that the doctor was negligent and provide proof of causation, which is difficult without help from other doctors.

In contrast to arguments involving violation of non-malfeasance, in which the burden of proof is on the patient, physicians must prove that they provided proper information and obtained proper informed consent [2345]. This makes it easier for a patient to file a lawsuit in South Korea.

Why is informed consent important in aesthetic surgery?

The doctor-patient relationship in the field of aesthetic surgery is different from the traditional doctor-patient relationship [678] because patients in this context have unique characteristics. Li et al. [9] classified aesthetic surgery patients into 5 different types: (a) simple aesthetic-seeking, (b) strong-consciousness, (c) defect-exaggerated, (d) psychological-barrier, and (e) pathologic-personality type. Most patients in the field of aesthetic surgery are type (a), simple aesthetic-seeking patients, who have an especially high degree of autonomy because they do not suffer from a disease at the time of surgery, meaning that they do not need traditional medical treatment. They have full rights over their body, which means that they may choose to change their appearance for personal satisfaction. Therefore, doctors must respect their right to self-determination by providing proper information about the relevant procedures. As such, informed consent is considered more important in aesthetic surgery than in other medical specialties due to the unique nature of the doctor-patient relationship in this field.

Why do patients make accusations of insufficient informed consent?

Doctors have a duty to take the best course of action to minimize the risks associated with specific symptoms and situations. As such, malpractice is not automatically recognized, and even when medical malpractice does occur, it is extremely difficult for patients to prove. In such situations, patients may claim insufficient informed consent. Although South Korean medical law contains no explicit provisions regarding the obligation of explanation, precedents show that it is not just an ethical prerequisite to obtain valid consent from the patients, but rather a legal obligation [10]. Moreover, emphasis has recently been placed on patients' right to self-determination in South Korea, and it has been argued that patients must make medical decisions based on a detailed recognition of their own health status [11].

Regarding recent precedents, some doctors have lost lawsuits due to their informed consent procedures not being recognized by the court, although the doctors provided explanations and obtained consent prior to surgery. For example, doctors can be held liable if the preoperative explanation emphasized only the advantages of surgery or if some content was missed during the process of obtaining informed consent. As competition among clinics becomes more severe, doctors tend to emphasize only the aesthetic effects of cosmetic surgery, neglecting to provide explanations about complications or adverse effects. This often leads to patients agreeing to undergo surgery without giving serious consideration to the potential problems that can occur after surgery; in such cases, when complications do occur, patients may file suit. This pattern most likely occurs because the patients were not actually given the opportunity to deliberate about various treatment methods and to make a properly informed decision.

In this article, we analyze precedent cases involving insufficient informed consent among medical disputes regarding aesthetic surgery in South Korea. Through a review of the key legal criteria articulated in these judgments, we aim to increase awareness of the importance of informed consent and to present points of reference that can aid in the prevention of medical disputes stemming from insufficient informed consent.

METHODS

Cases involving damage claims from medical malpractice lawsuits were categorized to obtain accurate statistics for cases related to aesthetic surgery. The data analyzed in this study came from 137 civil cases related to aesthetic surgery involving insufficient informed consent that were handled in district courts with rulings entered between 1995 and 2015 and that were obtainable through a request for a copy of the written judgment.

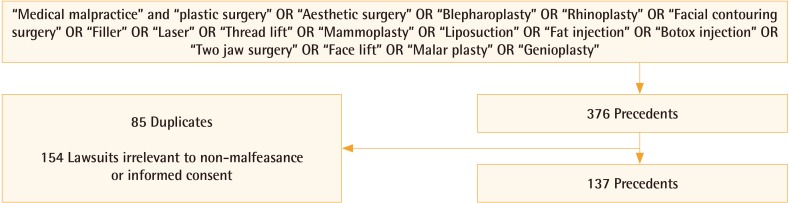

The precedent cases were collected through legal portal sites (Supreme Court Legal Information Service [glaw.scourt.go.kr], LAWnB [www.lawnb.com], and Google Scholar) using the search terms 'medical malpractice,' 'plastic surgery,' 'aesthetic surgery,' 'blepharoplasty,' 'rhinoplasty,' 'facial contouring surgery,' 'filler,' 'laser,' 'botox injection,' 'face lift,' 'thread lift,' 'mammoplasty,' 'liposuction,' 'fat injection,' 'two jaw surgery,' 'malar plasty,' and 'genioplasty' (Fig. 2). We analyzed raw data from 376 precedents for which the entire judgment was obtainable through a request for a written copy from the Supreme Court and the lower courts.

Study design, search terms, and results

A total of 137 medical litigation cases concerning aesthetic procedures during the period of the study were analyzed.

Based on the collected data, we analyzed types of procedures, types of complications, monetary amounts claimed and awarded, and the main points in the judgments against doctors. Data were collected and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis of the obtained data was performed using IBM SPSS ver. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between groups were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. In all analyses, P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

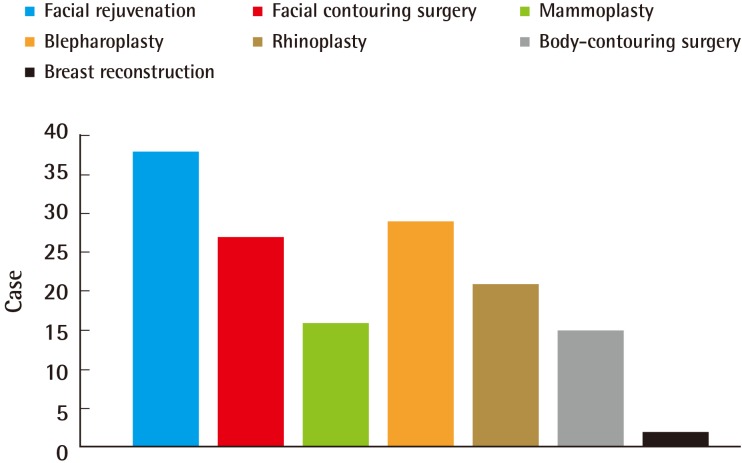

There were 137 cases of aesthetic surgery that were associated with insufficient informed consent during the study period. These cases included 124 female patients and 13 male patients. The mean age of the patients was 32.7 years (range, 16–67 years). We categorized the disputes according to types of aesthetic surgery (Fig. 3). The distribution of the cases according to type of procedure was as follows: facial rejuvenation (face lift, thread lift, filler injection, botulinum toxin injection, fat injection, and LASER therapy), 38 cases; facial contouring surgery (genioplasty, malarplasty, two-jaw surgery, and mandible angle resection), 27 cases; mammoplasty (augmentation, mastopexy, and reduction), 16 cases; blepharoplasty, 29 cases; rhinoplasty, 21 cases; body-contouring surgery (liposuction and abdominoplasty), 15 cases; and breast reconstruction (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous free flap and implant-based), 2 cases. Since some precedents involved more than one type of surgery, the total number of procedures exceeded the total number of precedents.

Distribution of litigation according to surgery type

Facial rejuvenation included fat graft, face lift, filler injection, laser-based procedures, and scar revision. Facial contouring surgery included genioplasty, malar plasty, two jaw surgery, and mandible angle resection. Mammoplasty included augmentation, mastopexy, and reduction. Blepharoplasty included upper and lower blepharoplasty. Rhinoplasty included augmentation procedures. Body contouring included liposuction and abdominoplasty. Breast reconstruction included transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flaps and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps.

Geographical distribution of the precedents in this study shows a high concentration in the capital city, Seoul. Ten million people reside in Seoul and 54% of plastic surgeons work there. Gyeonggi-do, the region immediately around the capital, has 12 million people but only 12% of plastic surgeons work there. Court precedents evaluated in this study show that there were 93 cases in Seoul, but only 5 cases in Gyeonggi-do (Fig. 4). The highest number of claims concerning care involved primary-level local clinics (113 cases), followed by secondary-level local hospitals (17 cases), while the lowest number involved tertiary-level university hospitals (7 cases).

Population, surgeon, and lawsuit geographical distribution

54% of total plastic surgeons are working in the capital city, Seoul and the 12% are working in the Gyeonggido, which is the most populated state in South Korea. There is difference between the number of population and the number of plastic surgeons; however, the number of lawsuit cases are similar to the number of plastic surgeons.

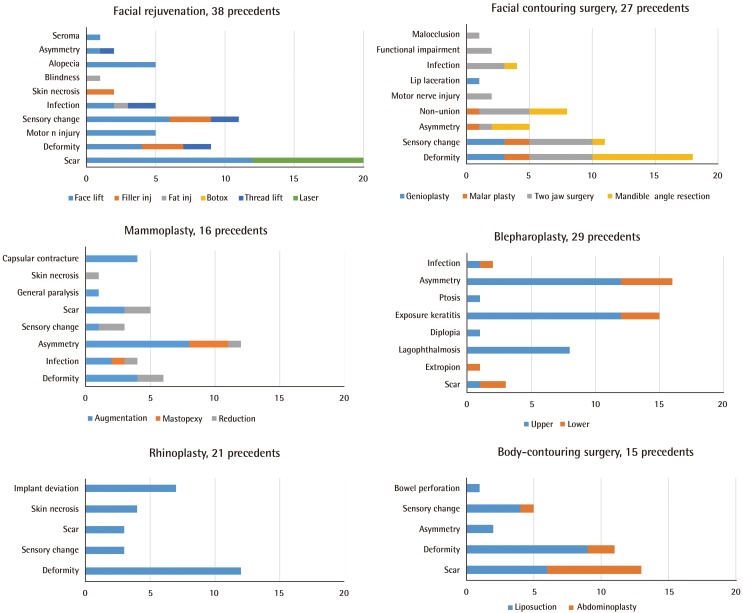

Several causes of patient dissatisfaction were found, and these were the major reasons that they filed a lawsuit (Fig. 5). The most frequent cause of dissatisfaction was the presence of a postoperative deformity, which was a factor in 22% of cases. The second most frequent was scarring, which played a role in 17% of cases, and the third and the fourth most common were asymmetry (14%) and infection (6%).

Complications by surgery type

The procedure with the most complications was facial rejuvenation (61 complications, 24%), followed by facial contouring surgery (52 complications, 20%), and blepharoplasty (47 complications, 18%). The most frequent complications and causes for dissatisfaction were deformities, scars, and asymmetry, which could be addressed by providing sufficient preoperative information about the expected outcomes and maintaining good rapport.

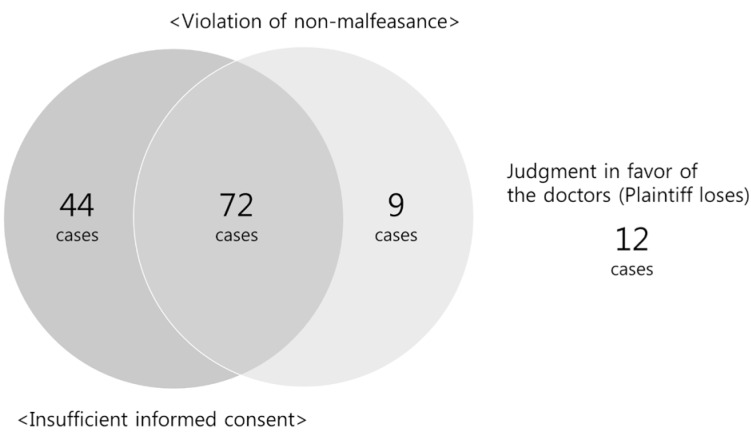

Among the total of 137 cases involving insufficient informed consent, insufficient informed consent alone was recognized in 32% of the cases (n=44), while in 53% of the cases (n=72), both medical malpractice and insufficient informed consent were recognized (Fig. 6).

Venn diagram of the medical litigation cases

Among the 137 cases we examined, 44 cases had a finding of insufficient informed consent alone, 72 cases had a finding of both medical malpractice and insufficient informed consent, and medical malpractice alone was recognized in 9 cases. The judgment was in favor of the doctors in 12 cases, while 91.3% of cases were found in favor of the plaintiffs (patients).

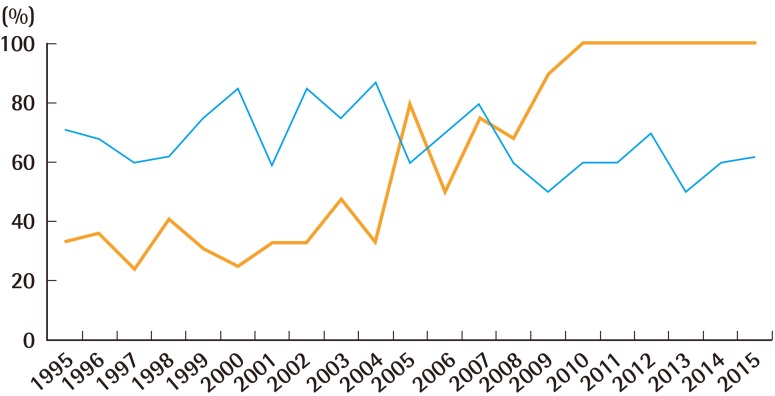

A relatively steady proportion of medical lawsuits was associated with the violation of non-malfeasance in the field of aesthetic surgery during the observation period. However, there were an increasing proportion of medical lawsuits associated with insufficient informed consent (Fig. 7).

The proportional changes in precedents by type

The gray line indicates an increasing tendency for medical litigation to involve insufficient informed consent. The black line shows a relatively uniform tendency in the percentage of medical litigation cases involving violations of non-malfeasance.

Among the total number of cases lost by the physician, there were 72 cases (58%) in which both malpractice and insufficient informed consent were recognized. Although there were a high number of cases in which both violations were recognized, statistical analysis showed that there was no relationship between the findings of malpractice and insufficient informed consent (Fisher's exact test, P=0.099, odds ratio, 2.182; 95% confidence interval, l 0.850–5.597).

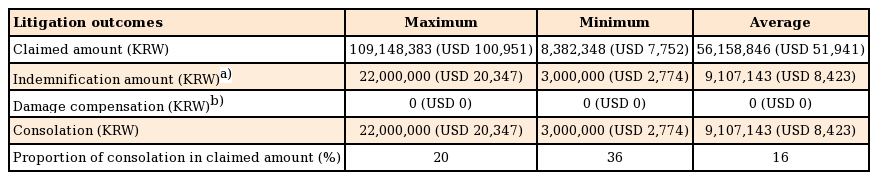

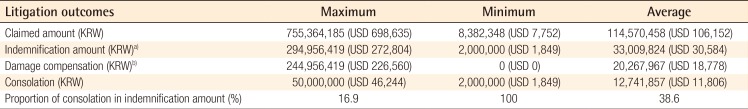

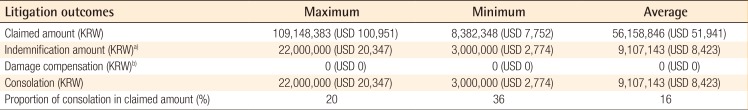

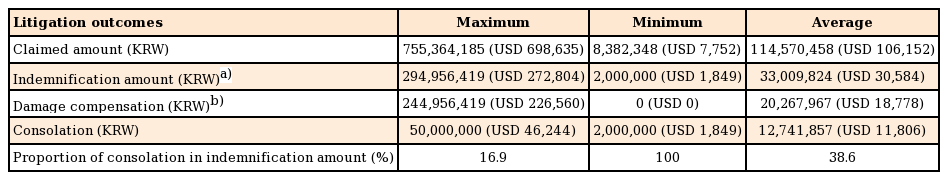

In cases in which both a violation of the duty of non-malfeasance and insufficient informed consent were recognized, the average amount claimed by the plaintiff was KRW 114,570,458 (USD 106,152), while the average amount of the judgment was KRW 33,009,824 (USD 30,584), corresponding to 28.9% of the amount claimed. Of the amount the judgment, consolation money accounted for an average of KRW 12,741,857 (USD 11,806), corresponding to 38.6% of the judgment (Table 1). However, in cases in which only insufficient informed consent was recognized (n=44), the average amount claimed by the plaintiff was KRW 56,158,846 (USD 52,037), and the average amount of consolation money was KRW 9,107,143 (USD 8,438), corresponding to 16% of the amount claimed (Table 2). A review of the main points from judgments against doctors showed that the act of obtaining consent based on information provided to the patient prior to surgery did not necessarily mean that the duty of obtaining informed consent was fulfilled, and that whether informed consent was recognized was decided based on whether the details of the risks and adverse effects were included on the consent form in writing. The courts rendered their decisions based on the opinion that "not having detailed explanations of the surgical method, surgical outcome, degree of difficulty, adverse effects, and risks in the consent form for the surgery corresponded to a breach of the patient's right of self-determination." This was not necessarily considered medical malpractice, but insufficient informed consent, for which physicians were ordered to compensate the patients for damages.

Litigation facts and outcomes in cases in which both violation of non-malfeasance and insufficient informed consent were recognized

DISCUSSION

The obligation of explanation means a doctor's obligation to explain the patient's medical condition and necessity of treatment before performing medical procedures. This obligation is currently referred to using the medico-legal term 'informed consent,' which originated in the US. Enshrining informed consent as an obligation can protect patients from harm by allowing them to make claims regarding doctors' breaches of this responsibility in circumstances where it is difficult to prove medical malpractice.

In medical malpractice litigation in South Korea, patients are required to prove the negligence or malpractice of the doctor, which is only possible with assistance from other doctors. However, because obtaining assistance from other doctors proved difficult, the civil law system established precedents for judgments involving insufficient informed consent based on the patient's right of self-determination, and began to institutionalize a system that allowed patients to win lawsuits without assistance from doctors. Therefore, the burden of proof for the fulfillment of informed consent falls on the doctor [12], which is the stance taken by the Supreme Court of South Korea. Therefore, doctors must prove that adequate explanation was given and that valid consent was obtained.

In the past, cases of death or serious complications were the most common sources of legal disputes, but such disputes have also often stemmed from subjective dissatisfaction, such as recent cases involving aesthetic procedures. This pattern can be seen as the result of unrealistic patient expectations and patients' increased awareness of their rights, and must be addressed through legal contracts. In our data, the majority of legal disputes were related to minor complications such as scars or postoperative deformities, which would not have resulted in claims if proper and sufficient preoperative explanation had been provided. These lawsuits were not related to the type of aesthetic procedure performed, nor the geographical region. However, most legal disputes were associated with primary local clinics because the majority of aesthetic procedures are performed in that setting in Korea.

An increasing number of medical lawsuits have involved insufficient informed consent, and we found 2 major reasons for this. First, proving malpractice by medical professionals may be difficult, but proving insufficient informed consent is relatively easy. Marchesi et al. [13] stated that many patients file a lawsuit to obtain compensation, even when the absence of surgical error has been proven, because they are confident that it is impossible to produce evidence of complete consent. Patients blame doctors for their discomfort, which is a typical side effect or complication following an aesthetic procedure, as if they have never been informed of the possibility of postoperative discomfort. Plaintiffs use it as a lawsuit strategy because they already know that it is almost impossible for doctors to prove perfect informed consent. As such, this has now become a typical judicial strategy of plaintiffs in South Korea, and it is very effective. Second, it is often the case that only the aesthetic effects of cosmetic surgery are emphasized, and explanations of potential complications or adverse effects are often neglected. Frequently, consent forms are prepared without specific content, and both the patient and the doctor prepare and complete the forms automatically. However, the existence of a consent form using standard wording does not serve as adequate evidence of proper informed consent.

Among the decisions examined in this study, 52% (n=72) of the total number of cases lost by doctors involved both insufficient informed consent and violation of the duty of non-malfeasance, so we need to further analyze whether there is a relationship between them or not. Moreover, the defendant may be worried about how the recognition of malpractice affects the recognition of insufficient informed consent because proving malpractice is much more difficult for the plaintiff than proving insufficient informed consent. However, the statistical analysis showed that there was no significant relationship between the court's decision regarding malpractice and insufficient informed consent. Although the fulfillment of informed consent itself does not affect the finding of malpractice by the court, the doctor will suffer emotionally and financially from the lawsuit if the court does not recognize that informed consent was obtained appropriately.

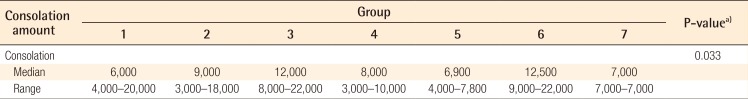

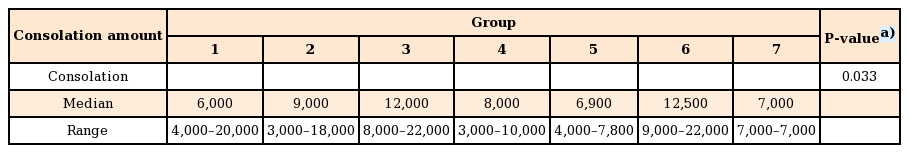

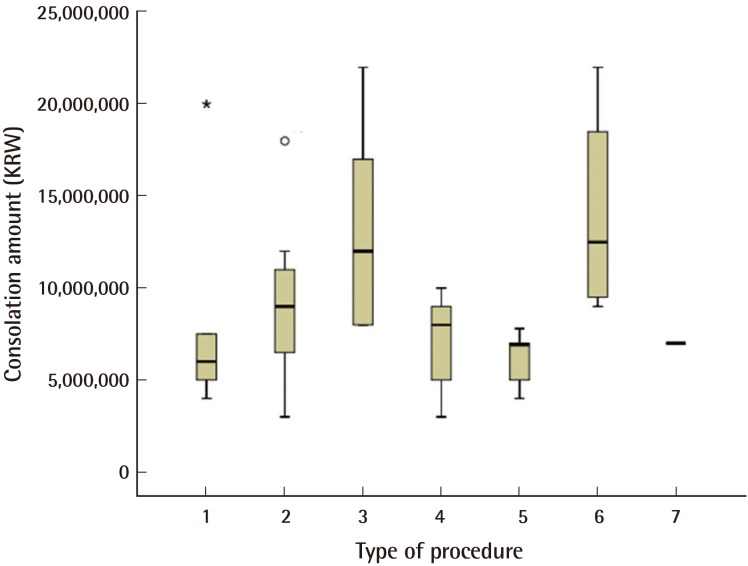

According to precedent in South Korea, when a doctor performs a surgical procedure without obtaining proper informed consent and the patient faces severe consequences, doctors are liable for making reparations for emotional damage. The argument is that if the doctor had provided information regarding the risks of the procedure, then the patient would have been able to exercise their right of self-determination to choose whether to undergo the procedure or to avoid any severe consequences that might occur. Therefore, the reparation to the patient reflects non-pecuniary damages, and the reparation amount in the legal dispute is set by the direct discretionary authority of the trial court after consideration of the patient's identity, age, family relationships, wealth, and education level. As such, since the reparation amount is under the authority of the trial court and the judge's discretion, it is not easy for the parties involved in the lawsuit to predict the awarded amount. Our statistical analysis found significant differences in the judgment amount according to the type of procedure (Table 3) (Fig. 8). When a patient experiences an unexpected complication, he or she may seek compensation for damages related to that complication. However, if the doctor's negligence is not recognized, the reparation amount is limited to mental damages, which not correspond to the patient's expectations. In this study, it is difficult to generalize about the consolation amount, but we found several cases in which the consolation amount exceeded the procedure fee. Therefore, doctors should change their methods, from explaining the positive effects only, to obtaining informed consent in order to minimize later financial expenditures.

Amount of consolation money according to surgery type in cases in which only insufficient informed consent was recognized (×103 KRW)

Consolation amount by procedure type

Significant differences were found in the consolation amount among the groups: 1, facial rejuvenation; 2, facial contouring surgery; 3, mammoplasty; 4, blepharoplasty; 5, rhinoplasty; 6, body-contouring surgery; and 7, breast reconstruction.

The method used to obtain informed consent is also an important consideration. First, it would be best for the doctor providing the treatment to explain the risks and benefits, not to other people such as family members of the patient, but to the patient directly. If the treating doctor is unable to directly give the information to the patient, it is permissible for another doctor to provide an explanation [14], but the other doctor should clearly explain the advantages and disadvantages of surgery. Second, in order to guarantee the patient's right to self-determination, the explanation must be given at a point in time when a certain level of diagnosis has been made. In aesthetic surgery, once the patient meets the doctor, decisions regarding consultation, examination, surgical method, and surgical timing are often made on the spot, which ultimately cannot be viewed as adequate fulfillment of informed consent. Third, regarding the extent of the explanation, the obligation of explanation increases with the invasiveness of the procedure. In addition, when an invasive procedure is urgently needed, such as in emergency medicine, the requirement for an explanation becomes less strict. For aesthetic surgery, which has relatively low urgency, the obligation of explanation becomes stronger. Regarding complications in aesthetic surgery, explanations must be provided if the complications, regardless of how rare they are, can have a substantial impact on the patient's body. Fourth, no official format exists for explanations; verbal explanations are widely accepted, although this can vary according to the level of trust between the doctor and patient. In the precedent cases, the existence of consent forms with standard wording was not recognized as a sufficient explanation [15]. Therefore, since the existence of a printed version of the consent form with standard wording may not be enough, verbal explanations should be annotated with markings such as underlines, asterisks, and/or circles indicating the parts of the text that have been explained.

This study shows that there have been an increasing number of lawsuits, with plaintiffs winning cases, on the grounds of insufficient informed consent based on subjective dissatisfaction, which is not related to aesthetic procedural malpractice. As a result, doctors have to assume an additional burden financially and emotionally. Therefore, informed consent must be viewed not only as an obligation for protecting the right of self-determination of patients, but also a means for protecting doctors themselves.

Notes

We would like to sincerely and profusely thank all members of our staff at Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital for their able guidance and support in completing this project.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.