Systematic Review and Comparative Meta-Analysis of Outcomes Following Pedicled Muscle versus Fasciocutaneous Flap Coverage for Complex Periprosthetic Wounds in Patients with Total Knee Arthroplasty

Article information

Abstract

Background

In cases of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) threatened by potential hardware exposure, flap-based reconstruction is indicated to provide durable coverage. Historically, muscle flaps were favored as they provide vascular tissue to an infected wound bed. However, data comparing the performance of muscle versus fasciocutaneous flaps are limited and reflect a lack of consensus regarding the optimal management of these wounds. The aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of muscle versus fasciocutaneous flaps following the salvage of compromised TKA.

Methods

A systematic search and meta-analysis were performed to identify patients with TKA who underwent either pedicled muscle or fasciocutaneous flap coverage of periprosthetic knee defects. Studies evaluating implant/limb salvage rates, ambulatory function, complications, and donor-site morbidity were included in the comparative analysis.

Results

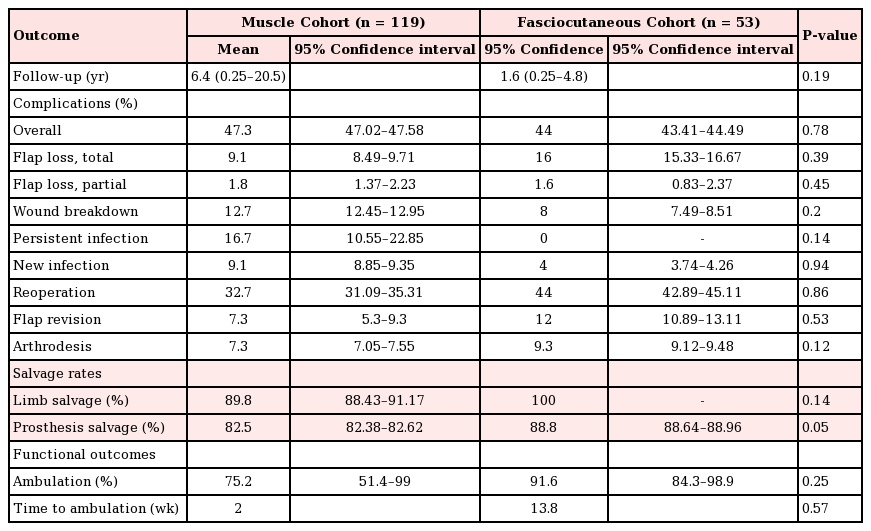

A total of 18 articles, corresponding to 172 flaps (119 muscle flaps and 53 fasciocutaneous flaps) were reviewed. Rates of implant salvage (88.8% vs. 90.1%, P=0.05) and limb salvage (89.8% vs. 100%, P=0.14) were comparable in each cohort. While overall complication rates were similar (47.3% vs. 44%, P=0.78), the rates of persistent infection (16.4% vs. 0%, P=0.14) and recurrent infection (9.1% vs. 4%, P=0.94) tended to be higher in the muscle flap cohort. Notably, functional outcomes and ambulation rates were sparingly reported.

Conclusions

Rates of limb and prosthetic salvage were comparable following muscle or fasciocutaneous flap coverage of compromised TKA. The functional morbidity associated with muscle flap harvest, however, may support the use of fasciocutaneous flaps for coverage of these defects, particularly in young patients and/or high-performance athletes.

INTRODUCTION

Wound complications after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are multifactorial and result from a culmination of local, host-specific, and environmental influences. In general, systemic comorbidities (i.e., diabetes, collagen vascular disease, or obesity), chronic immunosuppression, smoking, and malnutrition retard wound healing and contribute to higher rates of incisional dehiscence [123]. Pre-existent scarring, fibrosis, and irradiation further compromise local perfusion, particularly in the setting of poor operative technique and/or excessive mechanical stress from premature mobilization [456]. Despite efforts to control modifiable risk factors, delayed wound healing affects up to 20% of knee joint replacements and increases the probability of periprosthetic infection, hardware exposure, and above-knee amputation [17]. Although infrequent, these outcomes have devastating implications with respect to the cost and duration of hospitalization, functional recovery, and quality of life for affected individuals [8].

Currently, there are no universal, evidence-based guidelines for the management of skin necrosis and/or complex soft tissue loss following TKA. Preventative measures (i.e., optimal incision placement, aseptic technique, tension-free closure, adequate early immobilization, etc.) offer the best opportunity for uncomplicated healing and rapid functional recovery [910]. If wound breakdown does occur, however, early plastic surgery consultation and prompt intervention optimize the chances for successful device and limb salvage. Systematic evaluation of patient comorbidities and wound-related factors including the extent and depth of involvement, presence of infection, and exposure of the implant and/or adjacent subfascial structures should guide the reconstructive plan as well as the need for hardware removal [311].

In the presence of actual or threatened hardware exposure, flap-based reconstruction is indicated to provide durable, well-vascularized coverage that can withstand the dynamic stresses of ambulation. The standard muscle flap for knee coverage historically has been the gastrocnemius muscle flap; however with the advent of local and free flap techniques, other fasciocutaneous flaps have become popular. Numerous options have been described, ranging from local fasciocutaneous or muscle flaps to pedicled or free perforator flaps, combined flaps, and composite tissue constructs [3111213141516171819]. Nevertheless, data directly comparing the functional performance, long-term salvage rate, morbidity, and quality-of-life outcomes among the various techniques are limited and reflect a general lack of consensus regarding the optimal management of these wounds. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to critically evaluate the spectrum of reported outcomes and morbidities associated with muscle versus fasciocutaneous flap coverage of periprosthetic knee defects in patients with TKA.

METHODS

Literature search methodology

A literature search was performed using the MEDLINE, Ovid, and PubMed electronic databases with the following search terms and Boolean operators: knee arthroplasty [OR] knee prosthesis [AND] exposed hardware [OR] infection [OR] wound healing [AND] surgical flaps [OR] myocutaneous flap [OR] perforator flap [AND] ambulation [OR] limb salvage.

Selection criteria

The article review and selection process was limited to English-language publications between January 1950 and February 2016. Studies were included if they reported outcomes following muscle and/or fasciocutaneous flap coverage of wounds resulting from infection or healing complications after knee joint replacement. An attempt was made to evaluate quality-of-life indicators following flap-based reconstruction in this setting; however, these data were uncommon and inconsistently reported among studies. Descriptive, technical, cadaveric, and/or animal studies, as well as those that evaluated techniques other than flap-based reconstruction, were excluded. As more recalcitrant wounds were thought to require microsurgical free tissue transfer for soft tissue management, free flap reconstruction was also excluded from the review to limit confounding factors. The titles and abstracts were independently scrutinized by 2 authors (J.M.E. and M.V.D.) to identify relevant articles for full-text review. The review protocol is not available for remote access at time of publication.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted: study characteristics, including first author, publication year, and level of evidence; the number and type of flaps utilized; indications for flap reconstruction; functional outcomes; complications; and rates of limb as well as implant salvage. The analyzed flaps were classified by tissue composition (i.e., muscle/musculocutaneous or fasciocutaneous/perforator). Objective functional outcomes, including ambulatory status and range of motion, were primarily assessed through physical examination alone or in conjunction with instrument-assisted methods and/or validated outcome scales.

The validated outcome scales included the knee society scale (KSS), Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC), and the short form-12 (SF-12). The KSS is a 2-part assessment that evaluates knee joint integrity and function separately on individual 100-point scales. The knee assessment component consists of 3 parameters: pain, stability, and range of motion. The functional assessment consists of walking distance and stair climbing. The WOMAC is a 24-question survey that assesses the condition of patients with osteoarthritis. The survey is divided into 3 items (pain, stiffness, and functional limitation) with a total score of 96. The SF-12 is a 12-item, patient-reported survey of overall health that is divided into physical and mental health sections [20]. The scoring is based on standardized patient populations, with a mean score of 50 (standard deviation, 10) in the North American population.

Assessment of methodological quality

The methodological quality of nonrandomized comparative trials and case series was assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) guidelines [21]. The MINORS guidelines consist of 12 indices, with each receiving a maximum of 2 points. Nonrandomized comparative trials can receive a maximum score of 24, while case series can receive a maximum score of 16. The MINORS guidelines are a validated instrument to assess the quality of nonrandomized comparative trials and case series in the surgical literature.

Statistical analysis and meta-analysis

To represent the power of each study included in this review and account for differences in the sample size among studies, weighted averages were calculated for means throughout this systematic review based on the number of patients in each study. Baseline comparisons between subgroups and the effect of flap type (muscle vs. fasciocutaneous) on rates of limb/implant salvage, complications, and functional outcomes were performed, when possible, utilizing the 2-tailed unpaired t-test and the chi-square test for data containing continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Confidence intervals (CIs) were set at 95% and calculated for descriptive variables such as limb salvage rates, complication rates, etc. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Limb salvage, device salvage, and complication rates were treated as dichotomous variables with their respective 95% CIs. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the modified Wald method for proportions [222324]. Cochran Q tests were performed and heterogeneity inferred from the calculated I2 values. Values of I2 >50% were considered to represent substantial heterogeneity. Forest plots are presented to summarize the data regarding primary outcomes (Figs. 1,2,3). Each horizontal line on the plot represents a case series included in the meta-analysis, with the length of the line corresponding to a 95% CI of the effect estimate. The effect estimate is noted with a solid black square, whose size represents the weight that the corresponding study exerted in the meta-analysis. The pooled estimate is noted as a diamond at the bottom of the plot. Publication bias is demonstrated with funnel plots for primary outcomes (Figs. 4,5,6). Effect estimates were presented according to study size and plotted against the rates of limb or device salvage. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and plots generated with DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada).

Forest plot of limb salvage

Pooled rates of limb salvage across all studies (Cochran Q=40, df=17, P<0.0001; I2=57.5). df, degrees of freedom; LCL, lower confidence limits; UCL, upper confidence limits; WGHT, weight.

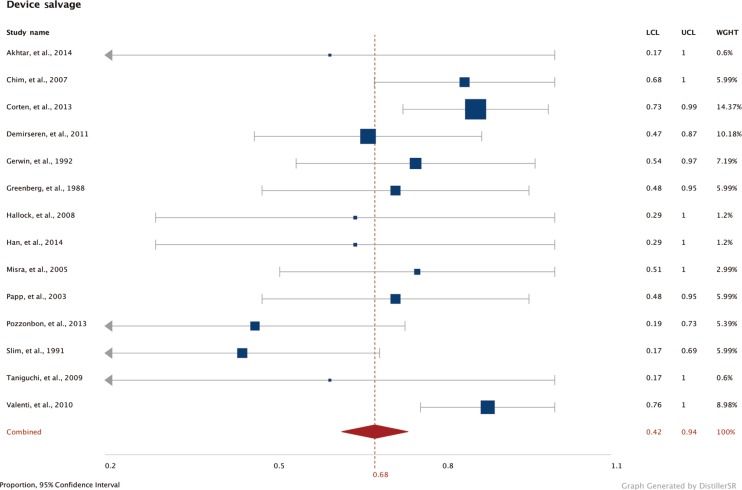

Forest plot of device salvage

Pooled rates of device salvage across all studies (Cochran Q=18, df=13, P=0.16; I2=62.5). df, degrees of freedom; LCL, lower confidence limits; UCL, upper confidence limits; WGHT, weight.

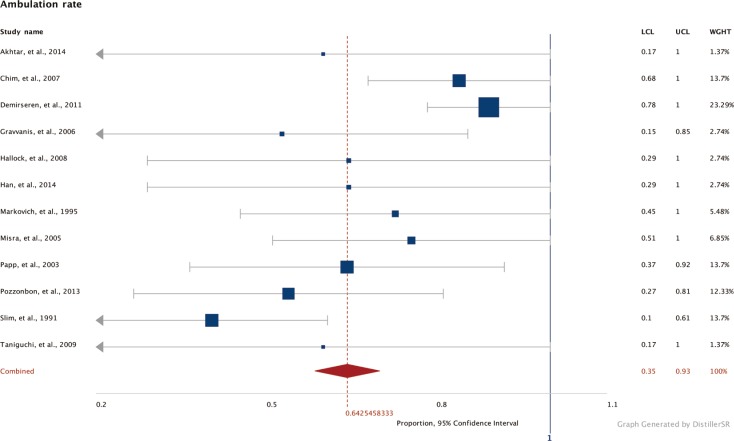

Forest plot of ambulation rates

Pooled rates of postoperative ambulation across all studies (Cochran Q=4, df=11, P=0.46; I2=1.75). df, degrees of freedom; LCL, lower confidence limits; UCL, upper confidence limits; WGHT, weight.

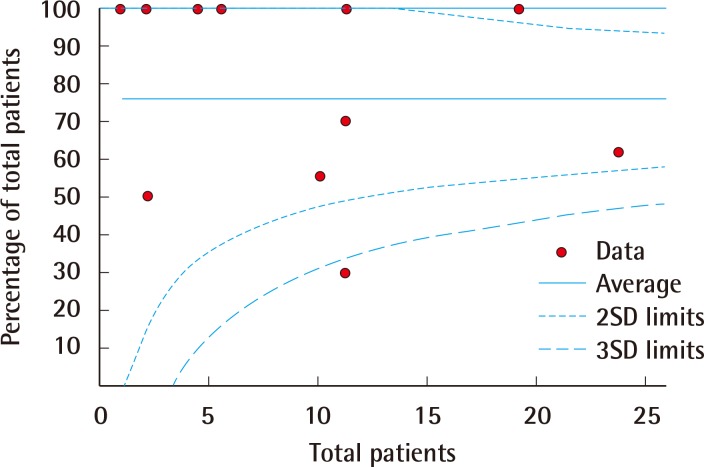

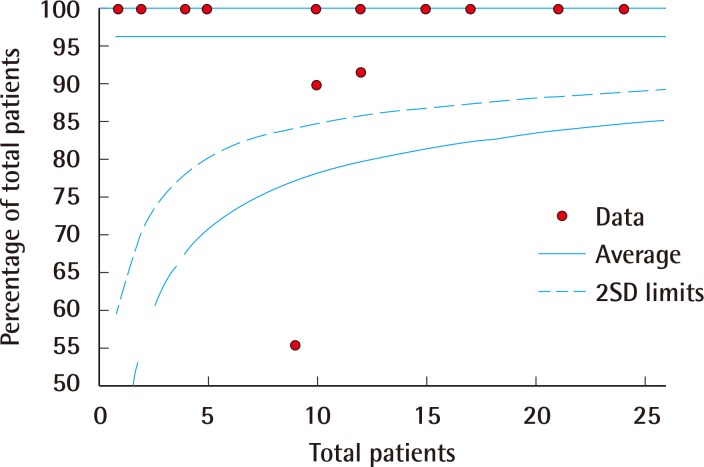

Funnel plot of limb salvage

Funnel plot representation of publication bias in the reporting of rates of limb salvage. SD, standard deviation.

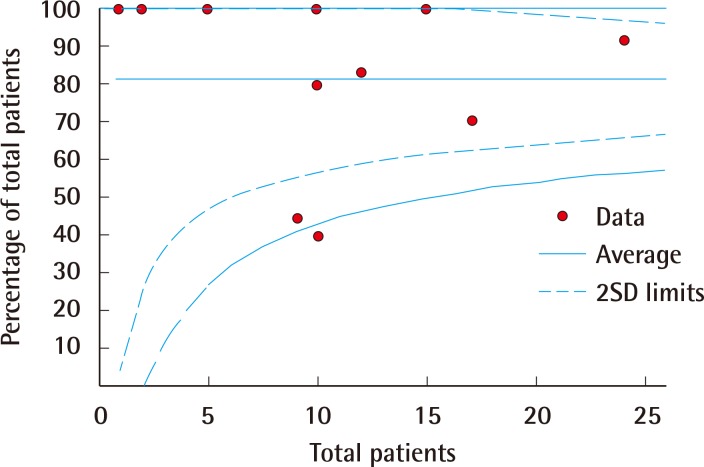

Funnel plot of device salvage

Funnel plot representation of publication bias in the reporting of rates of device salvage. SD, standard deviation.

RESULTS

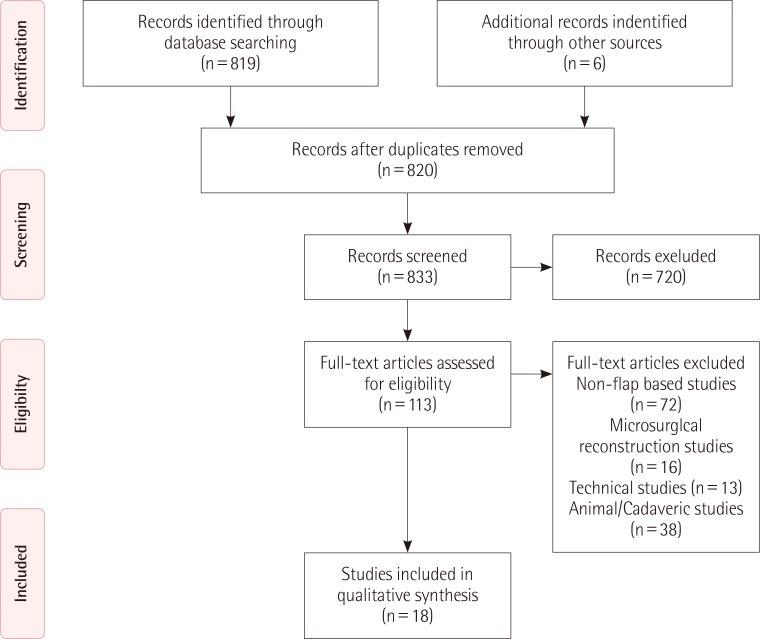

Study selection

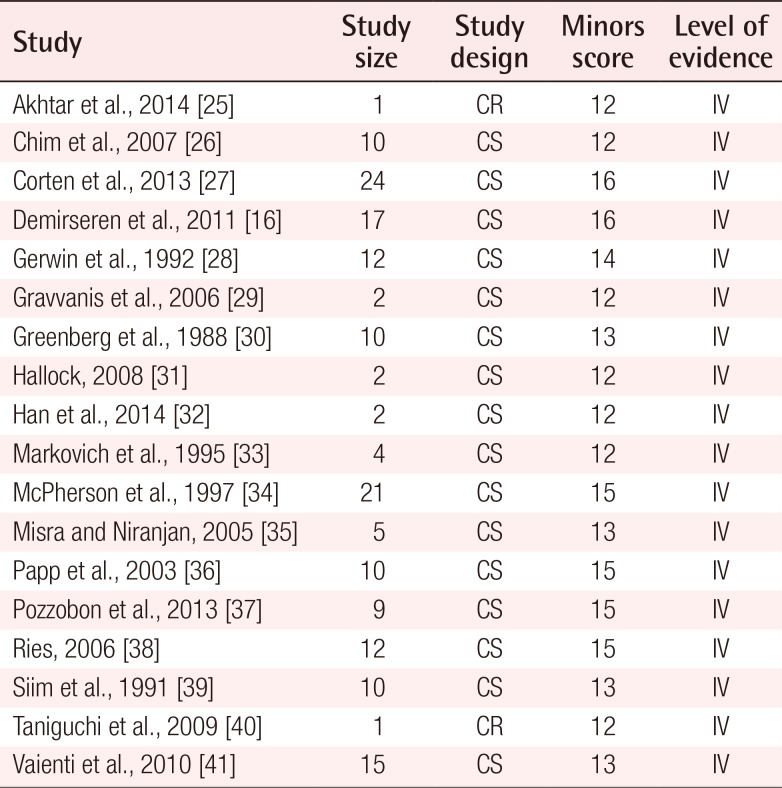

The initial search as previously described yielded 825 citations. Of these citations, 113 articles were selected and reviewed in their entirety. Following the application of the exclusion criteria, 18 articles were ultimately deemed appropriate for analysis (Fig. 7) [162526272829303132333435363738394041]. Of these 18 articles, 16 were case series and 2 were case reports.

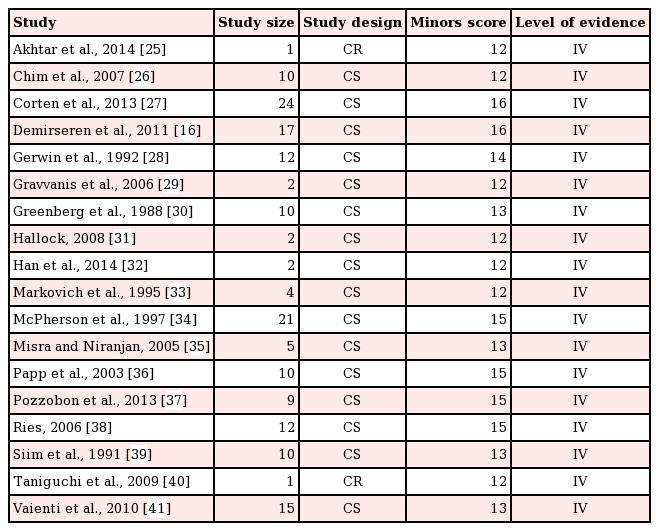

Assessment of methodological quality

The overall quality of the included studies was considered to be satisfactory for the purposes of this review. Each study scored above 12 points on the MINORS score (Table 1).

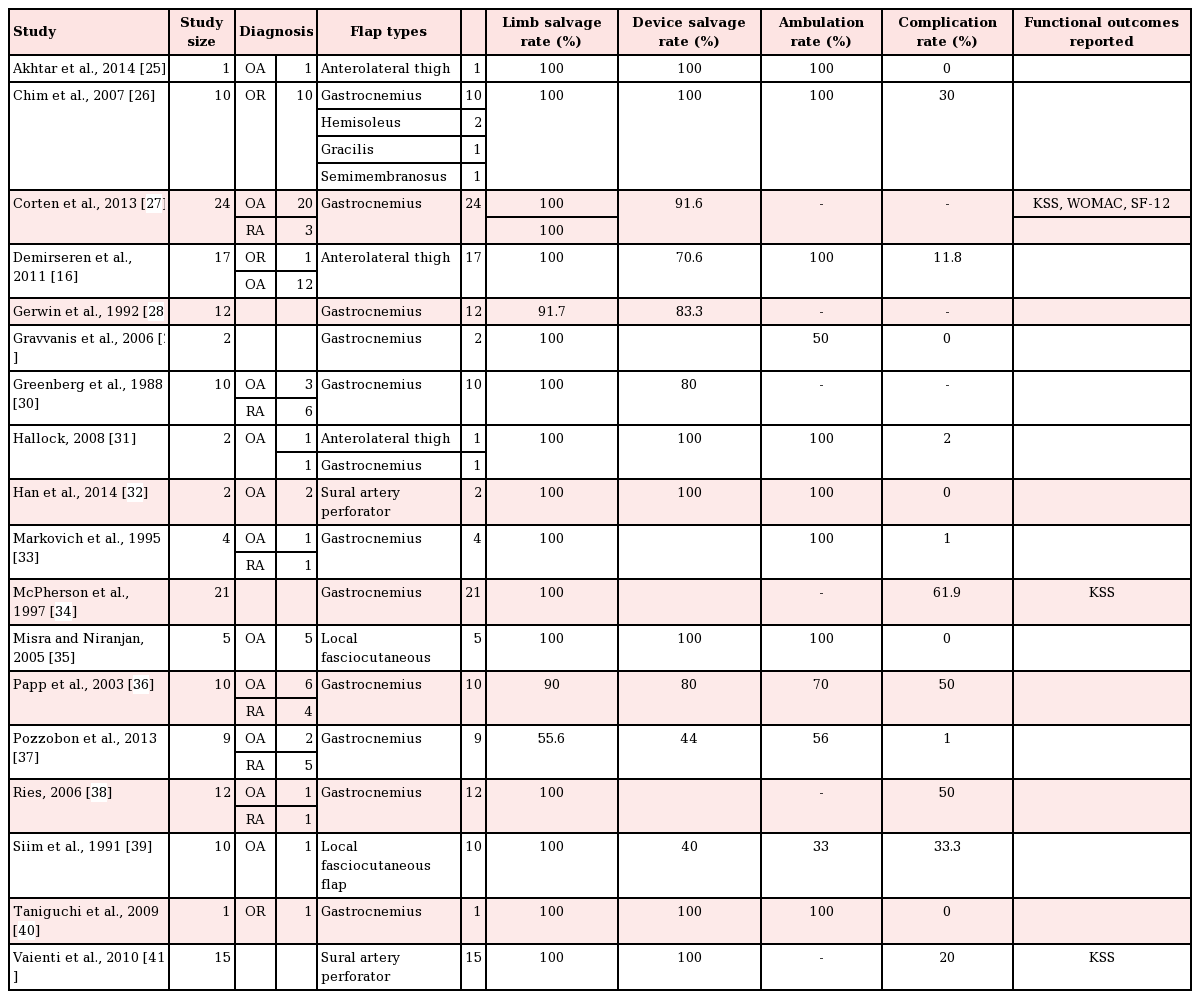

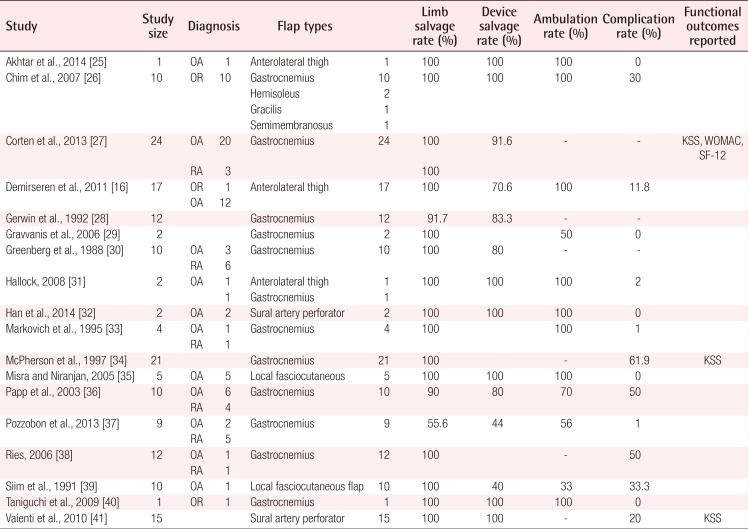

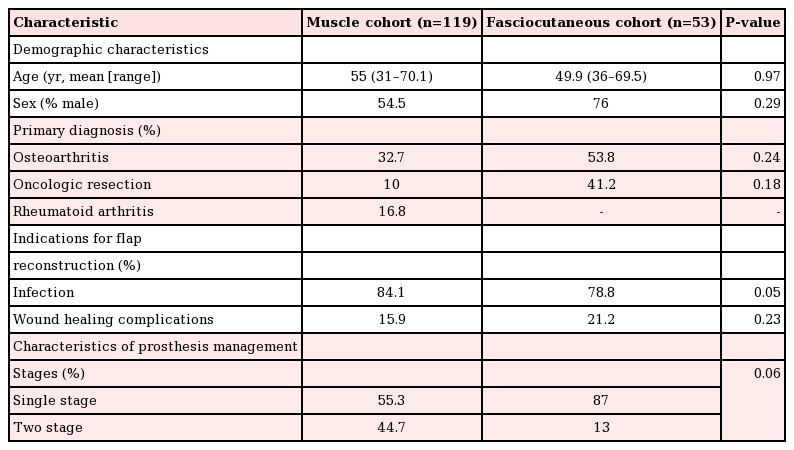

Pooled study characteristics

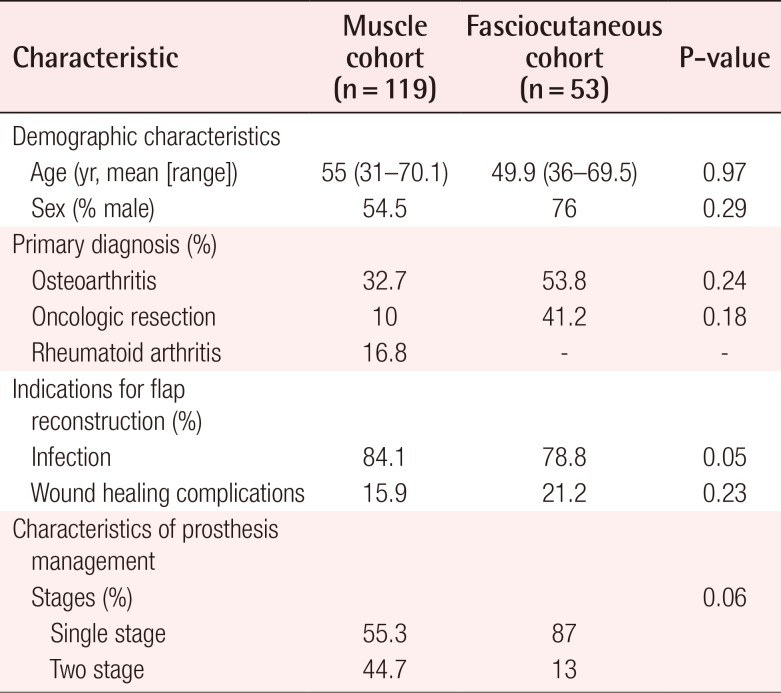

A total of 172 flaps were performed in 172 patients to cover TKA defects, including 119 pedicled muscle flaps and 53 pedicled fasciocutaneous flaps. The muscle flap coverage of knee defects was limited to gastrocnemius flaps, used alone (n=109) or in combination with hemi-soleus flaps (n=10). The fasciocutaneous flaps were primarily perforator-based and included pedicled anterolateral thigh flaps (n=20), sural artery flaps (n=17), a superior lateral genicular artery flap (n=1), and random-pattern local flaps (n= 5). The most common indications for TKA were osteoarthritis (32.7% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 53.8% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.24) and the oncologic resection of periarticular tumors (10% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 41.2% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.18). Indications for flap coverage were variable and included periprosthetic infection (84.1% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 78.8% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.05) and wound healing complications (15.9% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 21.2% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.23). The pooled proportion of limb salvage for all studies was 74.4% (95% CI, 0.49–0.99), the pooled proportion of device salvage was 68.1% (95% CI, 0.42–0.94), and the overall complication rate was 48.9% (95% CI, 10–67). Table 2 demonstrates the outcomes of all studies included in this review. No significant differences were found in the in demographic data, the indications for joint replacement, or the timing/etiology of failed arthroplasty among patients who underwent muscle versus fasciocutaneous flap coverage of periprosthetic knee defects (Table 3).

Comparison of population characteristics between patient cohorts undergoing flap coverage of total knee arthroplasty defects

The protocols for revision TKA following hardware infection and/or exposure varied among the studies. Single-stage management of compromised hardware, with thorough debridement of the involved joint and immediate soft tissue coverage, was reported in 55.3% and 87% (P=0.6) of the patients in the muscle and fasciocutaneous flap cohorts, respectively. In contrast, antibiotic spacer exchange and simultaneous flap coverage, followed by delayed hardware replacement (i.e., 2-stage revision TKA), was reported in 44.7% and 13% of patients who received muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps, respectively (P=0.6).

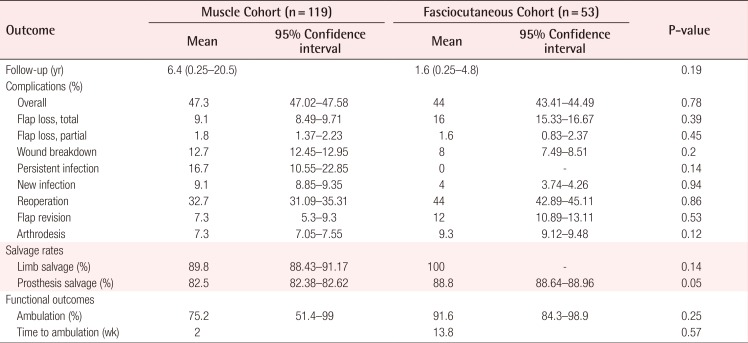

Surgical outcomes and complications

The mean duration of follow-up for the patients in the muscle and fasciocutaneous cohorts was 6.4 years and 1.6 years, respectively (P=0.19) (Table 4). The overall rates of implant salvage (82.5% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 88.1% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.05) and amputation (10.2% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 0% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.14) were comparable among patients in both groups. Salvage arthrodesis was performed in 7.3% and 9.3% (P=0.12) of the patients with failed arthroplasty and/or non-salvageable joints in the muscle and fasciocutaneous flap cohorts, respectively. The overall complication rates (47.3% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 44% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohorts, P=0.78) as well as total flap loss (9.1% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 16% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.39), partial flap loss (1.8% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 1.6% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.45), and wound breakdown (12.7% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 8% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.2) were similar between cohorts. In contrast, both persistent infections (16.4% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 0% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.14) and recurrent infections (9.1% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 4% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.94) were more common following muscle flap coverage of periarticular defects, whereas higher rates of revision (7.3% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 12% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.53) and reoperation (32.7% in the muscle flap cohort vs. 44% in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort, P=0.86) were associated with fasciocutaneous flaps. None of these observations, however, were statistically significant.

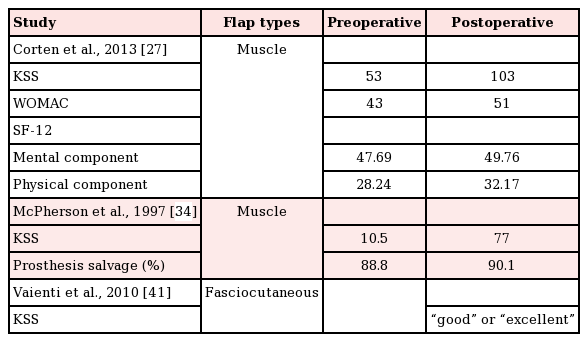

Functional outcomes

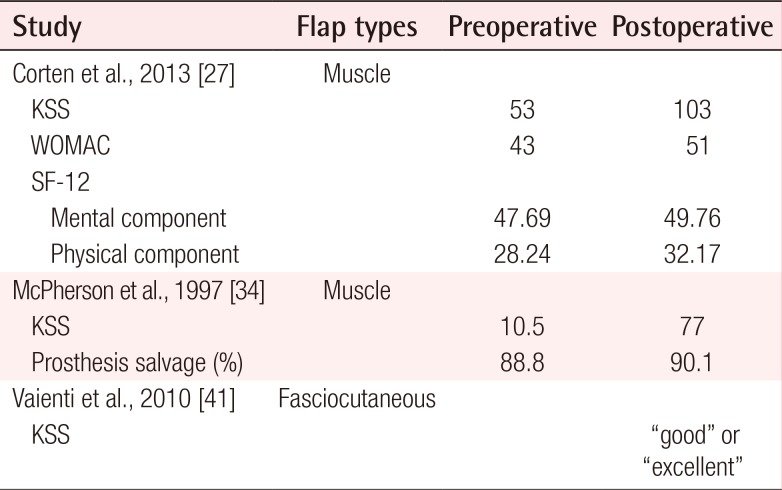

Notably, functional outcomes were sparsely reported, with only 3 studies (Table 5) utilizing validated outcomes scales, such as the KSS, WOMAC, and SF-12 [253139]. The mean postoperative knee motion among the 55 patients who underwent gastrocnemius flap coverage was 98.5° [2627282933343637]. These values, however, were not compared to preoperative baseline levels. Corten et al. [27] reported a 94% (53 vs. 103) increase between preoperative and postoperative KSS scores, among 24 patients who underwent gastrocnemius muscle flap coverage of knee defects. WOMAC scores were also reported by these authors, with an average increase of 19% over the preoperative baseline (43 vs. 51). The SF-12 scores reported by that study demonstrated a mean improvement of 4.3% (47.69 vs. 49.76) for the mental component and 14% (28.24 vs. 32.17) for the physical component. Another study of 21 patients who underwent gastrocnemius muscle coverage reported a mean postoperative KSS score of 77, in comparison to a preoperative value of 10.5 [34]. A single study reported functional outcomes for 15 patients who underwent sural artery perforator flap coverage using a validated scale. Their results indicate that patients had either good or excellent KSS scores following fasciocutaneous flap coverage; however, no quantitative numerical values were reported [31].

Meta-analysis

Forest plots of the 3 meta-analyses are shown in Figs. 2,3,4. Both limb salvage (Cochran Q=40, degrees of freedom [df]=17, I2=57.5; P<0.0001) and device salvage (Cochran Q=18, df=13, I2=62.5; P=0.16) demonstrated substantial heterogeneity among studies, with the former reaching statistical significance. Ambulation rates showed less heterogeneity among studies (Cochran Q=4, df=11, I2=1.75; P=0.046). Publication bias is presented in Figs. 5 and 6, and a significant bias was found toward the publication of findings with successful outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Delayed healing, wound dehiscence, and infection with associated soft tissue loss are potentially catastrophic complications that affect upwards of 20% of knee joint replacements [7424344]. Breakdown of soft tissue over a prosthetic joint replacement leaves the prosthesis and surrounding bone susceptible to exposure, infection, and potential loss of both joint and limb. As roughly 30% of patients who present with superficial postoperative wound infections ultimately seed their hardware, early and aggressive management of infection and/or wound breakdown is imperative to ensure stable soft tissue coverage of the prosthesis and prevent further complications [35]. When primary closure is difficult or impossible, more expansive wounds generally require either local fasciocutaneous flaps or pedicled muscle flaps to obtain adequate coverage [11142845464748]. No consensus has been reached on the optimal coverage of these defects, and the results from our review of the current literature show no significant differences between the coverage options in terms of rates of device/limb salvage, complications, persistent joint infection, reoperation, arthrodesis, or amputation. These findings suggest that both muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps may offer comparable outcomes in the reconstruction of periprosthetic TKA wounds. We argue, therefore, that flap selection in these circumstances may break free from historical paradigms and take into account patient-centered factors such as functional morbidity and quality of life.

Historically, the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles have served as the workhorse flaps for the coverage of periarticular knee defects due to perceived benefits in the vascularity of muscle flaps [11]. Previous studies on animal models, however, have demonstrated equal or greater improvements in recipient-site perfusion with the application of fasciocutaneous flaps [4950]. In addition, the observed effect that this improved vascularity may have on healing outcomes is mixed. In an experimental goat model for chronic tibial osteomyelitis, Salgado et al. [50] found no significant difference in the incidence of recurrent disease at 1 year following debridement and coverage between muscle (n=13) or fasciocutaneous (n=13) tissue. Similarly, retrospective reviews of patients who underwent either muscle or fasciocutaneous flaps for coverage of traumatic lower extremity wounds showed little difference in the bacterial count, rates of osteomyelitis, and quality of wound healing between flap types [515253]. Our data suggest that no significant differences are present in the rates of wound healing or infection between these 2 flap types, which may shift the discussion of flap selection to focus on other, more patient-centered factors.

At issue is achieving a level of postoperative function acceptable to patients who had previously undergone joint replacement as a means to improving quality of life. The harvest of muscles of the posterior compartment of the calf is not without consequences in terms of postoperative loss of function that may not be seen with fasciocutaneous flap harvest. This is particularly important in ambulatory patients and/or high-performance athletes. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles are important stabilizers of the ankle and knee and play a vital role in propelling the foot forward during the gait cycle. Previous reports have suggested that the use of these muscles in wound coverage can result in significant reductions in patient function. Knopp et al. [53] performed isokinetic testing on patients who had undergone local muscle flap transfer with a mean follow-up of 3 years. The authors reported a 21% reduction in foot flexion after gastrocnemius muscle harvest and a 20% reduction after soleus muscle harvest. Kramers-de Quervain et al. [54] reported 5 subjects who experienced significant decreases in ground-reaction forces and push-off forces in the operative leg after either gastrocnemius or soleus muscle flaps. They reported a calcaneal gait in up to 60% of the operative cohort. Furthermore, this objective functional deficit has been shown to correlate with patient-perceived disability. In a patient-centered, retrospective review by Daigeler et al. [55] of 218 patients who underwent local gastrocnemius muscle flaps for lower extremity wound coverage, 20% reported considerable difficulty using stairs, 28% were unable to stand on the operative leg alone, and 64% could not jump. Of the 42% of patients who could run postoperatively, 70% reported weakness when doing so. All patients who had undergone lateral gastrocnemius flaps experienced peroneal nerve palsy, with only 66% of patients fully recovering. Seventy-two percent of patients reported impaired sensibility in the operative leg. Not insignificantly, 13% of patients reported their function as insufficient or poor, and patients under 40 years old were more likely than older patients to rate their functional status as having worsened (P=0.03). Given these data, use of a gastrocnemius or soleus muscle flap may be a poor option in younger, more active patients whose functional demands often necessitate maintenance of sensibility, power, and plantar flexion.

The functional deficit that may result from muscle flap harvest contrasts with the results of fasciocutaneous flaps. Although technically more challenging, the harvest of fasciocutaneous tissue is associated with minimal functional morbidity. In a prospective study of postoperative function following 220 anterolateral thigh flaps, Hanasono et al. [56] reported no decrease in the range of motion of the donor leg and a 100% rate of return to the preoperative level of function. In an extremity that is already compromised, preservation of the leg musculature is imperative and may justify the more intricate dissection of fasciocutaneous flap harvest. Furthermore, a muscle-sparing approach may also allow easier flap re-elevation for staged revisions and implant exchanges, which are often required in the setting of infected prostheses. It is important to note that although our review included only pedicled flaps, microsurgical free tissue transfer may allow for more the frequent use of fasciocutaneous flaps, as various donor sites may be used for harvest and the recipient vessels surrounding the knee are large in caliber, facilitating microsurgical anastomoses.

In our review, we noted that clear and consistent reporting of functional and/or objective outcomes following soft tissue coverage of TKA wounds was lacking, with few studies reporting on practical outcomes such as ambulation, range of motion, and/or quality of life. Even fewer studies made use of validated outcome scales to measure these variables (KSS, WOMAC, SF-12, etc.). Only 3 studies in which functional outcomes were reported were identified in this review. Corten et al. [27] provided results from 3 validated scales (KSS, WOMAC, and SF-12) to show significant improvement in function after successful coverage of a compromised prosthetic joint with gastrocnemius muscle flaps. McPherson et al. [34] also reported improvements in KSS scores after gastrocnemius muscle flap coverage. Similarly, Vaienti et al. [41] reported good or excellent KSS scores in their series of 15 patients undergoing sural artery perforator flap coverage. Importantly, no study offered a direct comparison between muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps using validated outcome measures. Given that patients who undergo TKA are likely intent on returning to an active lifestyle, a validated assessment of postoperative function is paramount to achieving this end.

This study is not without its limitations. The heterogeneity among the data sources and lack of reported functional outcomes limits the role of statistical analysis as well as the ability to make meaningful comparisons between specific flap types. These factors are illustrated by the significant statistical heterogeneity found during the meta-analysis of the primary outcomes. In addition, differences in defect characteristics including size, depth, and exposed hardware existed among the reviewed papers. It can be presumed that fasciocutaneous flaps may have been selected in smaller or less complex defects, which may explain the favorable results seen in this group. It is important to note that the majority of patients in the fasciocutaneous flap cohort had undergone TKA following oncologic resection of the knee joint, while those in the muscle flap cohort underwent TKA for an unknown etiology or osteoarthritis. These differences, however, were not statistically significant. Selection bias within the published literature may have also influenced the results, as reflected in the high degree of heterogeneity among the published reports. For example, flap coverage differed between patients undergoing single- or 2-stage revision. Although the vast majority of pedicled fasciocutaneous flaps were performed following single-stage replacements, this trend did not hold true for the muscle flap cohort, which exhibited with a more split divide between single- and 2-stage reconstructions. These differences are likely explained by the presumed degree of infection and soft tissue breakdown in the patients who required more aggressive management, which may have contributed to selection bias. Furthermore, as in any systematic review, publication bias may be a factor in skewing the results, particularly in the surgical literature, which selects for the publication of results favoring an intervention. Lastly, the time to follow-up for functional outcomes varied widely, with longer follow-up noted in the muscle-only group (the mean follow-up duration for patients in the muscle and fasciocutaneous cohorts was 6.4 years and 1.6 years, respectively), which may have affected our analysis.

With the increasing number of joint replacements performed each year, a comprehensive investigation into the optimal management of compromised TKA is increasingly important. A critical look at the outcomes of various methods used to treat soft tissue defects following TKA will be necessary to identify the most effective and pragmatic approach to reconstruction, while optimizing functional prognosis, limb salvage, morbidity, and quality of life postoperatively. The results presented here demonstrate that the technical outcomes following reconstruction with either muscle or fasciocutaneous flaps are equivalent. Given the potential for functional morbidity from the use of muscle flaps, and all else being equal, we posit that fasciocutaneous flaps should be considered in a younger or more active patient population. Further research providing a direct comparison of functional outcomes between flap types must be undertaken using validated outcome scales.

Pooled rates of limb salvage across all studies (Cochran Q=40, df=17, P<0.0001; I2=57.5). df, degrees of freedom; LCL, lower confidence limits; UCL, upper confidence limits; WGHT, weight.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.